4.5 / Review

From New York: Wade Guyton OS

December 5, 2012Over the past decade, Wade Guyton has made an indelible mark in the field of painting, owing not only to the distinctiveness of his process—feeding linen through a large-format inkjet printer—but also to the dogged specificity of his project. From his first painting of a black X, drafted in Microsoft Word and printed across a magazine page in 2002, to his wall-length painting of alternating red and green bands produced specifically for Wade Guyton OS, the mid-career survey of his work now at the Whitney Museum in New York, Guyton has focused unerringly on his chosen subject: image transfer in the postindustrial age and the era of the personal computer.

Just two years into the 2010s, though, it is impossible to ignore the fact that the visual language of the home printer and scanner to which Guyton's practice has been so acutely attuned may be on its way out. With server-based file storage syncing our many digital devices and their contents together, the need to actually print things is becoming increasingly remote. It is not hard to imagine the all-too-familiar snags, anomalies, imperfections, and "losses" that texture Guyton's paintings becoming a thing of the past, replaced by the bright visual consistency of retinal scan displays.

But if Guyton were to move away from his inkjet printing, where would he go? Looking back, it is almost tempting to construe the artist's success as a deal with the devil: Contingent upon an intense commitment to certain technologies, Guyton's work was destined to become obsolete.

This is not a very promising impression to make in the mid-career survey of an artist only forty years old. In order to dispel it, Wade Guyton OS (OS stands for "operating system") must battle two prevailing interpretations: 1) that Guyton's oeuvre essentially boils down to one monolithic project—namely, painting within the prescribed parameters of word- and image-processing software and inkjet printing, with the software setting possible fonts, positions, and resolution and the printer setting color tones, print quality, and so forth; 2) that Guyton's language, though superficially derived from contemporary technology, is in fact essentially retrospective, motivated above all by reprising the tropes of the modernist moment (his 2007 series of rectangular black monochromes, for example, invites comparison to Rothko or Reinhardt). Only in dismantling these assumptions might the lingering sense of finitude give way to one of possibility.

On the whole, Wade Guyton OS happily avoids the trappings of museum didacticism that so often turn a mid-career survey into an interring retrospective. The show imposes on the viewer no prescribed path through Guyton's work. Rather, one encounters a scatter of freestanding walls, each often bearing as few as two paintings. As a result, possible paths through the exhibition proliferate, ones not necessarily dependent on chronology or theme. At most, each wall presents a sort of micro-project—an exploration of specific parameters like pixel resolution, color, or typographic form or of novel ways to abuse inkjet printers and linen—that in effect multiplies points of entry and reduces (at least to some degree) the sense of Guyton as a one-trick pony.

But the exhibition's suggested lines of thought do ultimately converge at a specific point, and significantly so, though it may seem at first glance to be an unexpected one: a re-creation of Guyton's Woodpile (2002). Consisting of a couple dozen wooden planks stacked against the gallery wall, Woodpile is, to say the least, an eyebrow raiser. It does serve as a reminder that Guyton, earlier in his career, dealt mainly in sculpture.

Wade Guyton OS, October 4, 2012 – January 13, 2013; installation view, the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Wade Guyton OS, October 4, 2012 – January 13, 2013; installation view, the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

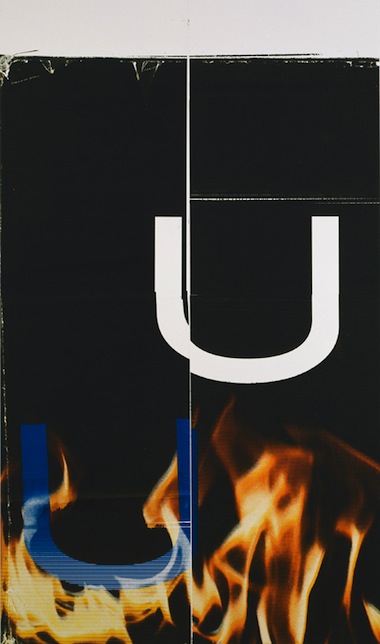

Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2006; Epson UltraChrome inkjet on linen; 90 x 53 in. Private collection. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © Wade Guyton. Photo: Lamay Photo.

Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2006; Epson UltraChrome inkjet on linen; 90 x 53 in. Private collection. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © Wade Guyton. Photo: Lamay Photo.

But there are several other sculptures included in the exhibition—for instance, U Sculpture (2007), a succession of mirrored, stainless steel Us of varying sizes, and Action Sculpture (2001), a Breuer chair frame twisted into a freestanding abstract object (yet still unmistakably a Breuer chair). While these other sculptural forms obviously address themselves to Guyton's pervasive interests in typeface and other such generic/iconic symbols, Woodpile is harder to place; it looks like just a lot of scrap material.

In fact, Woodpile's backstory is this: In the early 2000s, Guyton was working with minimalist sculpture and renderings in the form of photographs of existing architectural forms, overlaid with black Sharpie marks—what looked more like voids than proposed positive structures. Around this time, Guyton agreed to contribute a sculpture to a public art show in Brewster, New York, but he hit a creative block. Unable to devise a realizable concept of the sort he had been interested in, he turned to his immediate surroundings for inspiration. Thus he came across an abandoned pile of wood in an alley. He kept it exactly unaltered but for one shift—turning each piece on its head—and submitted the rotated pile as his work.

As an appropriative gesture that confines itself to preset boundaries (maintaining the relative positions of the pieces as found) and rigid manipulative actions (a 180-degree turn), Woodpile certainly prefigures the Microsoft Word– and Adobe Photoshop–drafted inkjet-on-magazine works that would succeed it. In these, too, Guyton would take found materials (such as preprogrammed fonts and magazine covers) and manipulate them through similarly rigid actions (enlargements, rotations, spacing, and hits of the "return" key). If Woodpile seems ridiculous while the inkjet work seems ingenious, no doubt this speaks of how evocative Guyton's inkjet aesthetic is. More than that, however, one could argue against interpreting Woodpile as a cohesive work in the first place, positing it as something else of significance: if not a bridge between Guyton's earlier concerns and his inkjet epiphany, then a momentous caesura in his practice—a point of productive impasse.

With the defining look of Guyton's paintings perhaps headed for obsolescence, it is reasonable to suspect that another creative impasse may be on the horizon for the artist. It is entirely appropriate, then, that Wade Guyton OS situates the viewer at Woodpile—a fulcrum from which one may look both backward and forward. Indeed, there are two couches, facing one another, placed beside Woodpile—a charmingly unorthodox accommodation and a clear, purposeful invitation for a viewer to sit and take inventory of Guyton's trajectories. Too often, museum exhibitions leave these moments out.

Wade Guyton OS is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York, through January 13, 2013.