3.4 / Review

Pissarro’s People

November 2, 2011Take away the more iconic images of Impressionism, whether sylvan glades or water lily umbrellas, and you might find something entirely new under the teeming surfaces of colorful brushstrokes. Organized by inveterate Impressionism scholar Richard Brettell and coordinated here by James Ganz of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Pissarro’s People at the Legion of Honor reconsiders an essential figure of the impressionist movement whose name is not as familiar as Monet’s or Renoir’s. Even the most astute students of art history may be surprised by this exhibition; at last we have an Impressionist’s vision of domestic life, agricultural work, and radical politics joined in a single presentation. Those who think that the best lessons on anarchism can be found at Occupy Wall Street are bound to discover that artists have been there long before.

There are about one hundred works in the show, which is divided between six rooms that are organized thematically and provide a kind of narrative flow. The first room contains intimate portraits of family members; viewers then move on to depictions of interior spaces and figure studies, followed by images of rural life. Paintings are interspersed with drawings and prints throughout, providing a multivalent viewing experience that upends the apparent simplicity of the blockbuster mechanism. This exhibition encourages serious and sustained looking, asking viewers to find visual connections between figures and to attend to a variety of techniques and mediums employed by the artist. There are studies for more complete works, such as the various preparatory sketches shown with The Harvest (1882), but there are also ink drawings, pastels, and prints that are finished works in themselves. Among the paintings, viewers can find oils, tempera, and gouache, demonstrating Pissarro’s experimental approach to technique. Though he rarely strayed far from home, Pissarro evoked his world through diverse methods and consistently pushed himself to rediscover the visions of rural and domestic life around him.

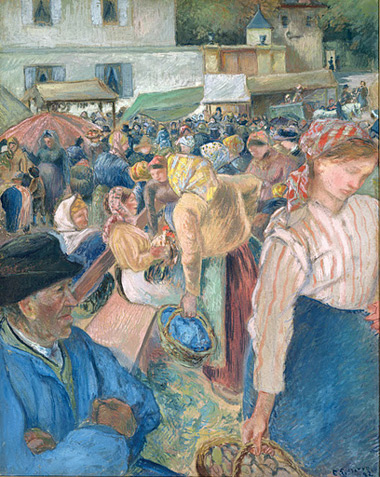

A gallery featuring images of rural markets focuses on some of the most complex multi-figure compositions of Pissarro’s epoch. The artist’s perspective places his viewers right in the thick of things, making it possible for us to view the multitude of characters and activities and to feel the bustle of the crowd. But his subject here is not the streets of Paris, as the Impressionists famously recorded, but the market square of his local village. Though the images were contemporary, one senses the artist’s nostalgia, or at least the valorization of a form of community in which each person has something to

Apple Harvest, 1888; oil on canvas; 24 x 29.13 in. Courtesy of the Artist and the Dallas Museum of Art.

The Marketplace, 1882; gouache on paper; 31.75 x 25.5 in. Courtesy of the Artist and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

offer and something else to take home at the end of the day. Trains and tractors—then harbingers of modern life—are notably absent. Yet, what at first appears to be escapism proves to be an indication of the artist’s political sympathies: his deeply held convictions about the interdependency and equality of individuals who can live together and trade with one another without hierarchy or oppression.

In the next room, viewers come face-to-face with a Pissarro never seen in a museum before this exhibition. Displayed under a vitrine, Les Turpitudes Sociales (Social Disgraces) (1889–90) is an album of ink drawings that the artist produced for his nieces’ political education, the last of which he smuggled to England himself to avoid interception by authorities. In this deeply felt work of political illustration are images of social calamities brought on by capitalism, paired with quotes from nineteenth-century anarchists and from the anarchist periodical La Révolte. The album is open to an image in which an archetypal capitalist stands on a pedestal in the middle of a square with a bag of money in his hands, while an impoverished crowd gathers around him seemingly about to expire.1 While Pissarro certainly held the strongest political convictions among the Impressionists, his views were moderate compared with those of French leftists in the 1890s, when the movement was so energized that one of its members assassinated President Sadi Carnot in 1894. Wall texts explain the genesis of French anarchism in the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and earlier utopians, as well as the anarchist mission: a life of dignity for all, devoid of property.

The final room displays an image of the utopia that would follow revolution as Pissarro imagined it. As is visible in the key work Apple Harvest (1888), the artist’s vision of paradise was grounded firmly on rural land, not in the city where he ended his days painting from hotel windows. It would seem that the paterfamilias of Impressionism imagined a life of rural work without the endless hours of labor and grinding poverty associated with it. The golden color on the gallery walls pushes for an upbeat ending. Still, once we acknowledge the very real social crisis of Pissarro’s time (and ours), it is difficult to get back into the phantasmagoria of aesthetic pleasure that museums usually offer. This exhibition reminds us that politics and art are by no means separate. For the imagination to thrive, artists need to think and dream, yes, but also to struggle a little.

Pissarro’s People is on view at the Legion of Honor, in San Francisco, through January 22, 2012.

________

NOTES:

1. Unfortunately, this image has not been released for use by the press, but you can see the entire album here: http://www.clarkart.edu/exhibitions/pissarro/content/slideshow-turpitudes-sociales.cfm.