2.4 / Review

Photographs and Not Photographs

October 21, 2010As a seminal Conceptual artist, Mel Bochner’s work has famously taken issue with semantics in works of art. His show and the accompanying catalog—on which the artist and Fraenkel Gallery collaborated closely—interrogate the systems inherent in representation. Bochner’s most compelling subjects remain the classical conventions of painting and drawing: measuring, support, perspective, and reproduction. He observes and quantifies the physical frameworks with which an artist may find himself in dialogue—the canvas, an institution, and the culture at large.

There is a pervasive sense that by bracketing the boundaries of these bodies of thought, one may indeed uncover glimpses of totality in the systems presented. This—along with the disproving of certain notions regarding photography’s inability to record abstract ideas—is the central theme of Bochner’s body of work in this exhibition. He examines the quantifiable and quantifying systems of the visual world, reflecting the institutionalized qualities of his subjects—often to uncanny effect.

Surface Dis/Tension, 1968; silhouetted C-print mounted on aluminum. Courtesy of the Artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Surface Dis/Tension, 1968; silhouetted C-print mounted on aluminum. Courtesy of the Artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Photographs and Not Photographs covers a wide range of materials and a number of periods of Bochner’s career, mainly the late 1960s and early ’70s, when he came to prominence alongside the likes of Sol LeWitt and Donald Judd. The exhibition also includes more recent works, such as a clownishly bright painting called No (2010), which features absurdly bubbly letters spelling out various words of rejection on an equally garish, blotchy-colored ground. Some of the more heavily manipulated photographs are in themselves a view of the abstraction of grid systems, perspective, and beauty; some are at odds with the simpler works that are focused on the act of measurement. Particularly, the economy of means demonstrated in 1968’s Actual Size (Face and Hand) goes up against plenty of darkroom manipulation in a series of aluminum-mounted C-prints. Surface Dis/Tension (1968) employs silhouetting, printing negative atop positive, and removing the skin of silver, processes that result in a polarized, textured, and quite sculptural effect. But Surface Dis/Tension and the Smear series (1968) inevitably yield their own topographical pretense—they’re still simply photographs. Their flatness creates a tense dialogue with the tenets of painting that Bochner perpetually tries to evoke. The grid—a device that renders our physical world into stark distances, vanishing points, and mathematics—is no longer hidden within a picture plane, but is made visible as a recurring theme. The descriptively banal Blah, Blah, Blah (2010) similarly makes me wonder: is an idea intensified in repetition or reduced to nonsense?

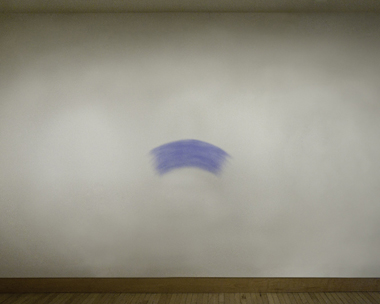

A wall painting mounted at SFMOMA last summer during the artist’s brief residency sticks with me as I take in this new exhibition. I’d watched Bochner and his assistants re-create No Thought Exists… (1970/2009) for a site-specific installation in the museum’s fifth-floor exhibition, Between Art and Life. Painted directly on the wall was a rough patch of blackboard-colored paint and, on top of that, the words “No Thought Exists Without A Sustaining Support.” The bottom edge of this pseudo-canvas was left to drip and melt with gravity’s pull. No Thought Exists… begs a number of questions. First, how might language—or thought alone—exist as a work of art? Second, is the wall of such a vast institution as SFMOMA really operating as a “sustaining” support? Formally, the work serves to highlight its own disregard for boundaries, and I found myself refreshed to witness these sentiments again at Fraenkel Gallery. Smudge (1968) is a work installed in Not Photographs as a site-specific confrontation with the body of the artist. Appropriately, Bochner’s body’s means of production—an arm is my best guess—remains as a trace in blue powder pigment, carrying enough poetic weight to exist solitarily in my mind for a few hours after I’ve left the gallery; I’m content to take home this memory, a breeze of blue dust. Barthes would agree that Bochner’s photography is still “tormented by the ghost of painting.”1

Smudge, 1968; blue chalk. Courtesy of the Artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Smudge, 1968; blue chalk. Courtesy of the Artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

There is a constant thread of antagonism in Bochner’s work, which is vital to his critique. I think of Misunderstandings (A Theory of Photography) (1970) as a framework for this exhibition; gathered neatly under glass are a number of note cards, each containing a key quote from such heavyweights as Wittgenstein, Duchamp, and Proust, as well as reference books, such as Encyclopedia Brittannica, which posits that “[p]hotography cannot record abstract ideas.” Bochner focuses on the disqualification of not only this statement but also many of the note cards’ ideas in a broad and sometimes maddening exhibition. Most clearly resounding the tone of rebellion are the particularly haunting Surface Dis/Tension and the oil on canvas work Blah, Blah, Blah. But in all his work, Bochner hints at the infinite while also pointing at the futility of this gesture. He’s interested in making visible the infinitely questionable means of measuring—and therefore believing in—the world around us.

Photographs and Not Photographs is on view at Fraenkel Gallery, in San Francisco, through October 30, 2010.