4.5 / Review

New Paintings and Not So New

November 30, 2012I’ve been thinking about the title of Rene Ricard’s recent show, New Paintings and Not So New. Each of Ricard’s paintings combines an image with a painted text that is frequently superimposed on the figures. Since a certain depth of phrase and enigmatic suggestion mark each text, it only seems proper to consider the show’s title. The oldest paintings in New Paintings, after all, are from 2011. Does the title playfully exaggerate the length of one year in Ricard’s fifty-year career? Or is it an exaggeration of the tried-and-true formal practice of juxtaposing text and image—or of the subjects of the paintings themselves, which often register as not so new, such as the ugly quaintness by which the phrase “[throwing] rocks at girls” might refer to wedding proposals?

Or is it, perhaps, the not-so-newness that is the larger point of these lush, strange, and ultimately dark paintings and poems? Ricard’s use of twentieth-century imagery suggests a world-historical sense of cyclical violence and abuse—one that is seemingly more destined to repeat itself than disappear. The suggestion of such violence in Ricard’s work, more often than not, is intuitive and abstract. And the anonymity of the subjects deepens this sense that spectacular forms of consumption and horror are universally recurrent, timeless, and non-specific in their acts of violence.

And yet in other cases, Ricard attends to a historicized geography in his paintings. Untitled: “Then Love Takes” (2011) shows a soldier’s face in the ruddy browns and greens of the camouflage uniform. The text reads, “+ then love takes you to faraway places ... Goa ... Angola ... Mozamb.” The irony in the juxtaposition of image and text in this case is painfully clear: this love is a Western drive for the violent expropriation of resources from other lands (in this case, former Portuguese colonies). Nevertheless, the soldier’s indeterminate nationality actually underscores the omnipresence of colonial hunger that “Then Love Takes” perversely calls love.

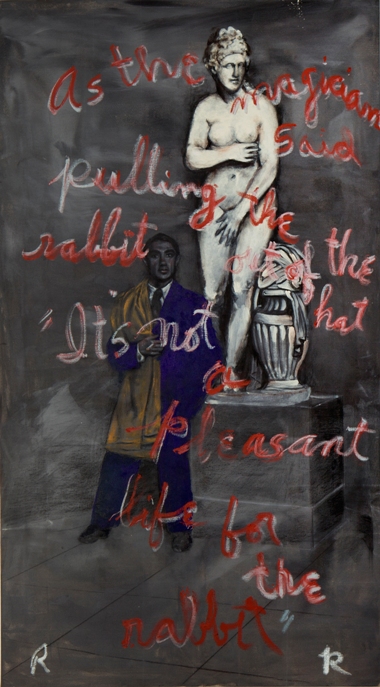

Despite the fact that the relative clarity of the cursive script, the proportional size of the characters, and the foregrounding of the text demand that the painting be read in some literal sense, Ricard has different techniques for pairing word and figure. In Untitled: “As The Magician..." (2011), much like in “Then Love Takes,” the text most closely resembles a caption, reading, “As the magician said, pulling the rabbit out of hat, ‘It’s not a pleasant life for the rabbit,’” over an image of a man next to a sculpture of a nude woman. The scene feels like it’s set in a museum, with a bit of noir atmosphere created by the erasure of the larger architecture surrounding the man and sculpture.

Rene Ricard. Untitled: “As the Magician...,” 2011; oil, chalk on linen. Courtesy of the Artist and Highlight Gallery, San Francisco.

Rene Ricard. Untitled: “As the Magician...,” 2011; oil, chalk on linen. Courtesy of the Artist and Highlight Gallery, San Francisco.

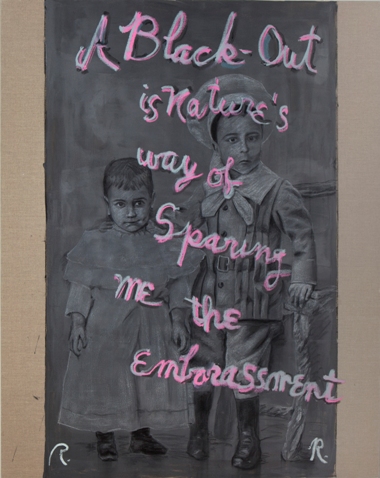

Rene Ricard. Untitled: “A Black Out," 2011; oil, chalk on linen. Courtesy of the Artist and Highlight Gallery, San Francisco.

Rene Ricard. Untitled: “A Black Out," 2011; oil, chalk on linen. Courtesy of the Artist and Highlight Gallery, San Francisco.

Yet while both figures look toward the viewer, the statue’s gaze seems focused on a distant point, and the man’s eyes meet those of a viewer. Thus, all three players in the drama of the painting (statue, man, and viewer) are given the opportunity to play the role of the rabbit, the mammal forever consigned to repeated extrication from a hat for the benefit of an audience hungry to laugh. The text obliquely describes the dramatic encounter of a viewer with the painting, without the gnomic provocation of “Then Love Takes.”

In other paintings, Ricard’s logic is more obscure, such as in Untitled: “A Black Out” (2011). Here, the text appears to refer to the proverbial shame and longing that follows a night of too much booze: “A Black-Out is Nature’s way of Sparing me the Embarassment.” Urbane, pathetic, and witty as a statement in its own right, the phrase becomes less direct when considered with the image, which depicts two young children, one of whom is dressed in a sailor costume. The figures seem to have been painted from a photograph, often an aid to memory. And yet memory is precisely what’s effaced by a blackout. At first glance, the juxtaposition of image and text suggests that a remembered image of childhood has been affected by the drunken night in question. But then again, might not the “black-out” refer to the fact that the photograph is reproduced in the painting with grays, blacks, and whites, potentially sparing the painter the risk of embarrassment in trying to represent adequately the original image in color? What’s more, the pairing of phrase and painting becomes less clear in light of how the artificiality of the sailor costume underpins the already uncanny association of “Nature’s way” with a liquor- or drug-induced blackout.

Still, consider the text without the image. If all the texts in New Paintings and Not So New were removed from the images and presented as poems, they would appear as slight and conversational epithets. They might even seem uncanny on account of a minimalism that erases any disambiguating context—like the scarcely perceived museum scene in "As The Magician." And yet, because they are incorporated into the composition of the paintings, each poem transfigures its painting with a new stratum of semiotic information. Each painting acts as a visual register that partakes of a poetic logic, in the linguistic sense of poetics, where the function of language deemphasizes context while privileging the encounter with messages themselves.

Ricard’s incorporations, however, are not seamless. Whether the text and image are more obviously related or their connection is more obscure, each serves to complicate the other. The image only charades as visual context with the potential to demonstrate the meaning of the text, and the text only charades as a caption that will discursively inform the viewer about the image. This disjunction is mirrored by a darkness that is common to many of the works in New Paintings and Not So New. Neither poetry nor painting can adequately represent the violence of contemporary life, whether it is the violence of a love relationship (such as in Untitled: “Sometimes it is okay” [2012], which reads “Sometimes it’s OK to throw rocks at girls”) or the imperialistic impulse.

In Untitled: “The World Was...” (2011), a young boy from an earlier era holds a ball behind the words, “The world was discovered by mistake but it was no accident.” I read the ball as metonymic for all the forms of competition that this young male is socialized to aspire toward and love. His expression suggests rage, grief, resignation, and remorse. The world is discovered in the shift between extremes of affect and intention, image and sentiment.

New Paintings and Not So New is on view at Highlight Gallery, in San Francisco, through December 9, 2012.