3.8 / Review

Indelible Fables

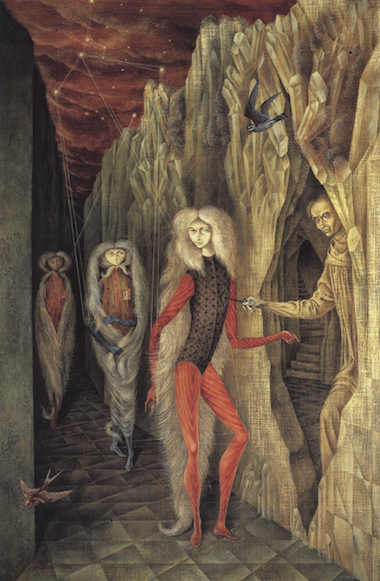

February 1, 2012Who is the elegantly waifish woman—with high cheekbones, flaxen hair, and sharp almond eyes—pictured in some of Remedios Varo’s paintings? Judging from the vitrine containing vintage photographs and other ephemera in this rare gem of an exhibition, it could be Varo herself, in stylized self-portrait, or at the very least, an idealized proxy. Almost always, this figure is furtively looking over her shoulder, as if she were evading capture or seeking escape. While it is unclear who or what might be pursuing her, always visible are what she may be trying to escape: dark, confining spaces composed of high walls and quasi-Gothic architecture that enclose Varo’s figures in complex, claustrophobic pictorial mazes.

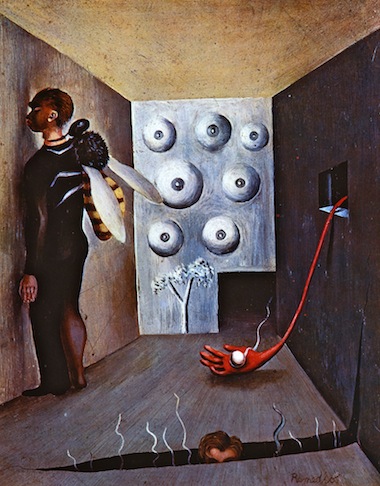

The eight paintings and six drawings included in this exhibition date from 1936 and include excellent examples from every decade of Varo’s short career (she died in 1963 at the age of fifty-four). The work titled The Double Agent from 1936 is of particular interest, as it is one of the very few that survive from the years that Varo lived in Paris (1937–41), where she had fallen under the spell of Surrealism. The painting is quite small and painted with lustrous oil applied to a copper plate, which makes it appear to have been executed in egg tempera. It depicts the grotesque scene of a woman being sexually assaulted by a large and hideous insect, and there is something both urgent and inconsistent in the way that the paint is applied to these two figures: it jumps rather abruptly from conventional descriptive modeling to hastily expressionistic passages. Both figures inhabit a room that seems to have been rented from Salvador Dali, a maison imaginaire, portentously decorated with seven disembodied breasts, mounted on the far wall in a way that eerily prefigures the sculpture that Eva Hesse would make three decades later. This painting also sports the brightest and most complicated color of any painting in the exhibition; in Varo’s mature style, her color became subdued into moody earth tones of rust and reddish brown. In this aspect, her work was influenced by the pre-Columbian sculpture that she found so fascinating in her adopted home of Mexico, where she lived for her final twenty-two years, after she exited Paris just prior to the Nazi occupation.

One special treat of this exhibition is its inclusion of six of Varo’s drawings, almost all of which seem to have been

Retrato del doctor Ignacio Chávez (Portrait of Dr. Ignacio Chávez), 1957; oil on masonite; 37 x 24 in. Courtesy of Frey Norris Contemporary & Modern, San Francisco.

L'agent double (Double Agent), 1936; oil on copper; 9.75 x 7.75 in. Courtesy of Frey Norris Contemporary & Modern, San Francisco.

continuously worked as preparatory studies for paintings. At least one of these drawings is clearly related to an adjacent painting, Portrait of Dr. Ignacio Chavez (1957). The similarities and discrepancies between the two reveal much about Varo’s working method, which is clearly rooted in deliberate compositional strategies rather than any Surrealist immersion into the unconscious. The drawing shows Varo’s reworking of the relationship between the two figures, repeating the female in the painting three times to suggest a psychoanalytic assembly line, where the male doctor applies his special key to the hearts of three identical women.

What is particularly remarkable about Varo’s work is the way that it harks back to Gothic painting of the tenth and eleventh centuries, particularly that of Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1178), with its emphasis on involuted and idiosyncratic pictorial spaces and crisply stylized allegorical figures. The associations that might be made between Surrealist and Gothic painting have never been properly explored, but we might remember that André Breton once remarked that he had never—nor would he ever—visit Italy. (No remnants or rebirths of Classical civilization for him!) Certainly, there is a secret affinity between Surrealism and the medieval worldview: both prized spiritual ambition and both deplored worldly materialism. But this analogy is problematic for a number of reasons. One of these is the fact that women were never allowed by their male Surrealist counterparts to have a spiritual status because they were relegated to the roles of muses in service to male artists. To their credit, those women rebelled against that position and made art that was every bit as insistent on realizing their own “subjective realism” as that of their male colleagues.

In fact, the feminist mantra proclaiming that the personal is the political seems to have clear Surrealist roots, and few painters then (or now) made art that was more personally idiosyncratic than Varo did. But her work never stopped at that point. Instead, it revealed a disciplined focus, the necessary ingredient for translating the personal into tightly wrought allegories that may have been too subtle and sophisticated to be overtly political but were nonetheless prophetic of a great many things to come. Indeed, although Varo’s work can at times err on the side of excessive stylization, it still might contend as a worthy art historical precursor to the New Old Master painting. Donald Kuspit coined this genre, proclaiming it a necessary antidote to what he called postart spectacle—pseudo-conceptual art designed to make symbiotic teams of artists and curators of large institutions seem democratically relevant in the sphere of vision that is in fact governed by the mass media. For Kuspit, New Old Master art “brings us a fresh sense of the purposefulness of art,” and Varo’s enigmatic Gothic revivals still have the power to guide us to an understanding of that purposefulness.1

Indelible Fables is on view at Frey Norris Contemporary & Modern, in San Francisco, through February 25, 2012.

________

NOTES:

1. Donald Kuspit, The End of Art (Cambridge, U.K.; Cambridge University Press, 2004), 192.