4.17 / Review

From Philadelphia: Each One as She May

June 13, 2013 Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Thierry De Mey. Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich, 2002 (video still); 35mm transferred to color video, sound; 58 minutes. Courtesy of the Artist and Rosas.

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Thierry De Mey. Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich, 2002 (video still); 35mm transferred to color video, sound; 58 minutes. Courtesy of the Artist and Rosas.

All of the literature printed for the excellent exhibition Each One as She May at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Philadelphia begins with a quote by Gertrude Stein: “Repeating is the whole of living and by repeating comes understanding.” Curated by five undergraduate students (Alina Grabowski, Chloe Kaufman, Andrew McHarg, Vincent Snagg, and Iris-Louise Williamson), their professor (Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw), and an ICA curatorial fellow (Jennifer Burris), the exhibition delves deeply into repetition—as a mode of production and what profit it renders—using a very small sample of works by only three artists.

Because the exhibition was created as part of a University of Pennsylvania class, the process of putting the show together was based on intense research. On October 27, 2012, the curatorial team visited the studio of Glenn Ligon to discuss his 1998 solo exhibition, Glenn Ligon: Unbecoming. In the course of their conversation, Ligon played the group some of Steve Reich’s phase compositions, in which a sample is recorded, repeated, and layered so that the sounds begin in perfect sync but slowly shift and diverge. As the recordings progress, once-clear words or notes overlap and become unintelligible as they build to a crescendo of pure noise before slowly sliding back to their original legibility.

This fortuitous introduction was the seed of Each One as She May, a small but extremely substantial show that includes the work of Glenn Ligon, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, and Steve Reich. In the upstairs project space at the ICA, the work is laid out very simply: drawings by Ligon cover one wall; opposite this is a large-scale digital projection of four dances by De Keersmaeker; and in the adjacent hallway, patrons can listen to two of Reich’s phase compositions. Though materially and compositionally diverse, the three components work together like facets of a gemstone: they all belong to the same foundational whole but reflect its brilliance in different directions.

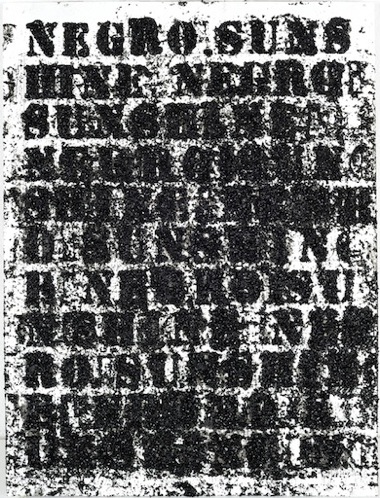

The twenty-nine oil-stick-and-coal-dust drawings in Glenn Ligon’s Studies for Negro Sunshine (each made between 2008 and 2012) are hung in a neat grid, but the stenciled letters are not clear; they’re smudged, smeared, and blown-out, like a silkscreen that’s printed using too much ink. The phrase, which quotes Gertrude Stein’s 1909 short story “Melanctha: Each One as She May,” also belies the imposed order: the words negro sunshine are repeated without regard to the conventions of word breaks, so that the individual phrases read: NEGRO SUNS/ HINE NEGRO/ SUNSHINE/ NEGRO SUN/ SHINE NEGR/ O SUNSHINE. Following the logic of Reich’s phase compositions, the clarity of the words dissipates into a confused mess. And like the sound compositions’ shift from certainty to ambiguity, the overall grid formation of the works attempts to impose order, but the erratic arrangement of words counteracts the pattern. What viewers experience depends greatly on whether they stand back and focus on the whole or whether they move closer to inspect a single drawing. The understanding that comes with repeating, in this case, is complicated. These works are the physical consequence of a man grappling with racism and its effects; by repeating the words, Ligon summons a terrible specter, yet by blurring the words to incoherence, he also rejects the nightmare.

Working more directly with the principles of Reich’s compositions, the choreographer and dancer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker stages three duets and one solo in Thierry De Mey’s film Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich (2002). Each of the dances is accompanied by one of Reich’s compositions: Piano Phase (1967), Come Out (1966), Violin Phase (1967), and Clapping Music (1972). Piano Phase begins with two dancers, lit from the front to make three silhouettes on the wall behind them. The silhouettes on each side correspond to only one dancer, but the silhouette in the middle is made from two perfectly overlapping shadows. To accomplish this, the two dancers must move in sync; and so it’s the middle silhouette that most closely mimics the idea of Reich’s phases, as it shifts in and out of coherence. Though the dancers initially swing their arms and rotate their bodies in unison, their movements eventually fall out of coincidence; although they no longer match each other exactly, their movements correspond to the music so that, overall, their modifications are still in keeping with the intention of the composition. Another work, choreographed to Violin Phase, is a solo dance on what appears to be a sand-covered platform in a forest. The camera tracks De Keersmaeker as she leaps, swirls, and glides to trace a symmetrical pattern through the sand. At one moment the camera captures her close-up in mid-twirl, and as she turns there is a brief smile on her lips—evincing the deep pleasure of an artist who has complete mastery of her craft. Indeed, given De Keersmaeker’s precise, hypnotic, and emotionally powerful dances and moments such as this one—a kind of grace that provides an empathic connection to the dancer—this viewer could have watched these works all day. Here, the “living” part of Stein’s quote is emphasized, where repetition casts a spell of fierce joy.

In the hallway adjacent to the project space, two recordings play Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966). Because De Keersmaeker’s dances are choreographed to Reich’s compositions—so that a viewer who watches the entire film has already been listening to Reich’s music for almost an hour—the placement of these recordings can at first feel like an afterthought, yet it’s important to experience Reich’s investigations divorced from the attention-absorbing visuals of the dances.

The young curators are to be especially commended for the thought-provoking depth of this exhibition founded on a very tight concept. Individually, the works of Ligon, De Keersmaeker, and Reich show different modes of repeating and understanding. Together, they make an excellent case for the strength, necessity, and ferocity of repetition and variation.

Glenn Ligon. Study for Negro Sunshine #46, 2010; oil stick, coal dust, and gesso on paper; 12 x 9 in. Courtesy of the Artist.

Glenn Ligon. Study for Negro Sunshine #46, 2010; oil stick, coal dust, and gesso on paper; 12 x 9 in. Courtesy of the Artist.

Each One as She May: Ligon, Reich, and De Keersmaeker is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, in Philadelphia, through July 28, 2013.