Review

Chuck Close: Important Works on Paper from the Past Forty Years

November 4, 2013Spend enough time in art school (read: any amount of time), and discussions that emphasize the evolution of one’s creative practice become routine. At the end of a challenging graduate program, newly minted artists are expected to present a body of work demonstrating not only their technical strengths and aesthetic concerns, but also a discernable trajectory through which the work has developed.

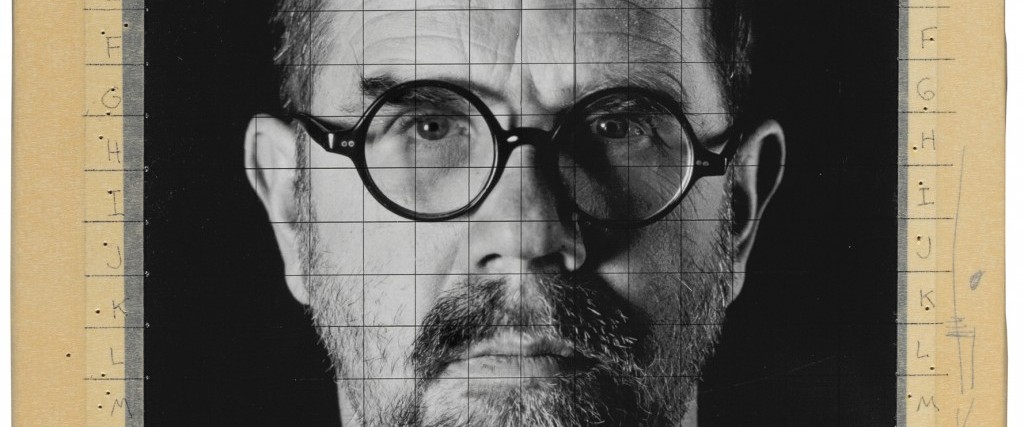

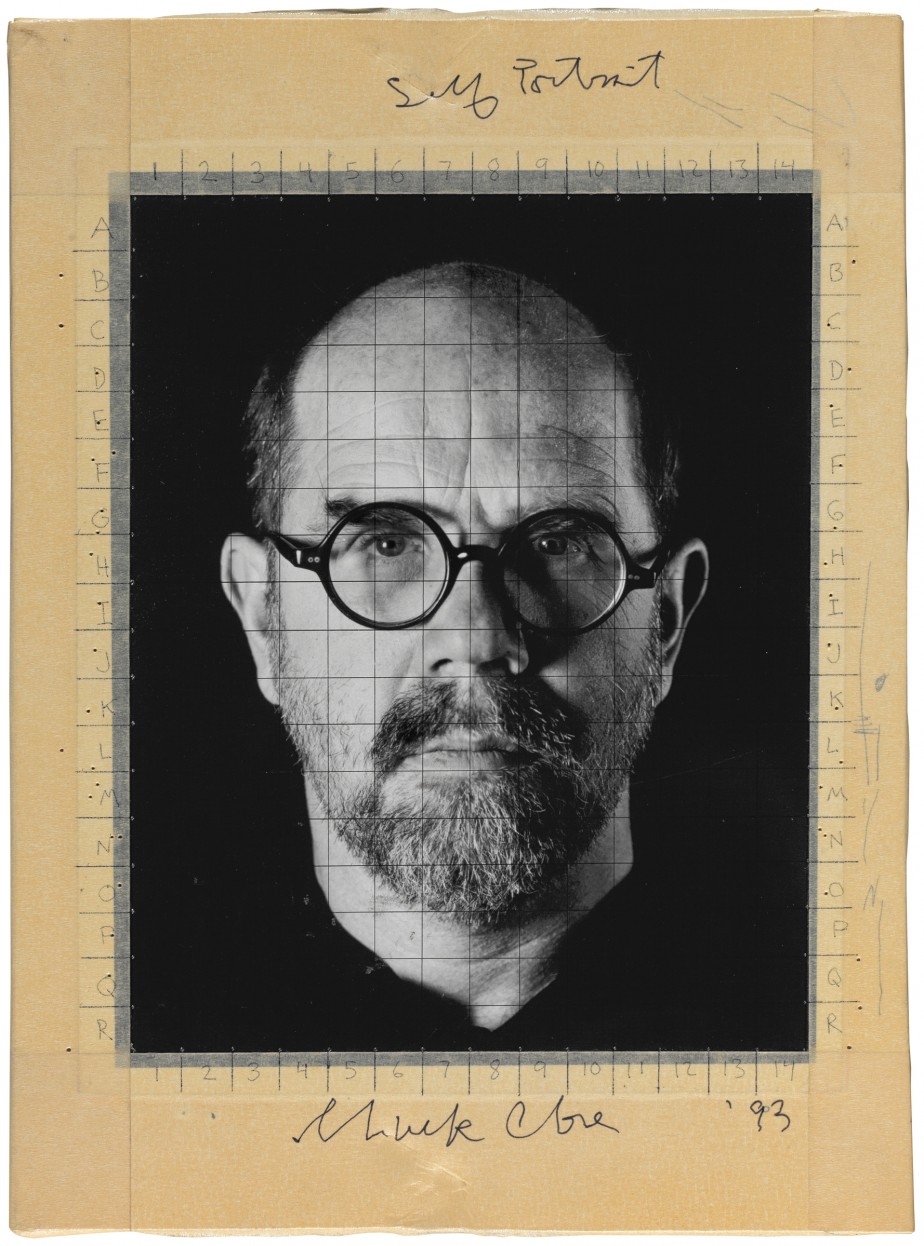

That somewhat problematic notion was squarely in mind while I looked at Chuck Close’s work, currently on view at John Berggruen Gallery, precisely because his practice has not changed radically over the course of 40 years. His method is straightforward: print and mount a photograph, mark it with tape and pencil until a grid is formed, then meticulously translate the visual information in each square in varying media, including mezzotint, watercolor, ink and graphite, and pressed paper pulp, until a reproduction of the image is complete. What emerge are portraits of the famous and the unknown and—in a cultural milieu that valorizes near-constant change—an argument for placing value on nurturing a focused practice.

Chuck Close. Self-Portrait (Maquette), 1993; black-and-white Polaroid with ink and tape mounted to foamcore; 9 3/8 x 7 3/8 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and Pace Gallery. © Chuck Close.

Chuck Close. Self-Portrait (Maquette), 1993; black-and-white Polaroid with ink and tape mounted to foamcore; 9 3/8 x 7 3/8 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and Pace Gallery. © Chuck Close.

Close’s works on paper, which address a range of concerns including issues of identity and the problem of representation in photography, are hung in rough chronological order. Older pieces, some dating to the early 1970s and the beginning of his career, are hung opposite contemporary work, illustrating the wide breadth of his material interests. When interviewed on the eve of an exhibition opening at the Akron Art Museum in 2009, Close stated that in 1967 he set aside his paintbrushes—the tools of an early photorealistic painting practice that earned him sustained critical attention—in order to experiment with media for which he had no facility. He took up an airbrush and began working with rubber stamps, screen printing, finger painting and, more recently, Jacquard tapestry. Though Close never abandoned traditional painting altogether, the self-imposed variable of working with unfamiliar media helped define the exploratory nature of his work. One of this exhibition’s strengths is the inclusion of works that bear the mark of that experimentation: pencil lines, inky fingerprints in the margins, printing notations, and tape that has yellowed over time.

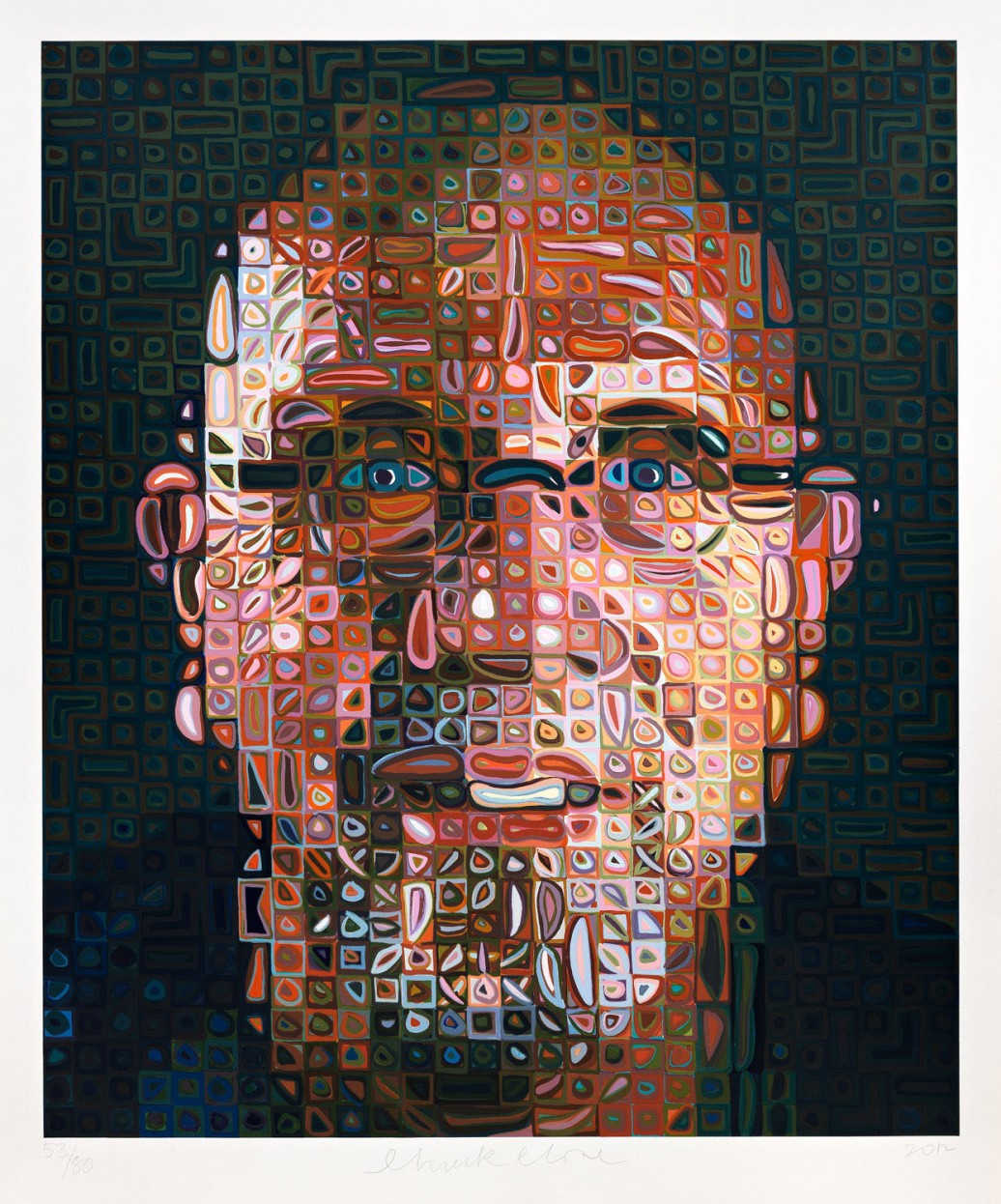

Chuck Close. Self-Portrait Screenprint 2012, 2012; silkscreen in 246 colors; edition 20/80; 59 1/2 x 50 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and Pace Editions Inc. © Chuck Close.

Chuck Close. Self-Portrait Screenprint 2012, 2012; silkscreen in 246 colors; edition 20/80; 59 1/2 x 50 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and Pace Editions Inc. © Chuck Close.

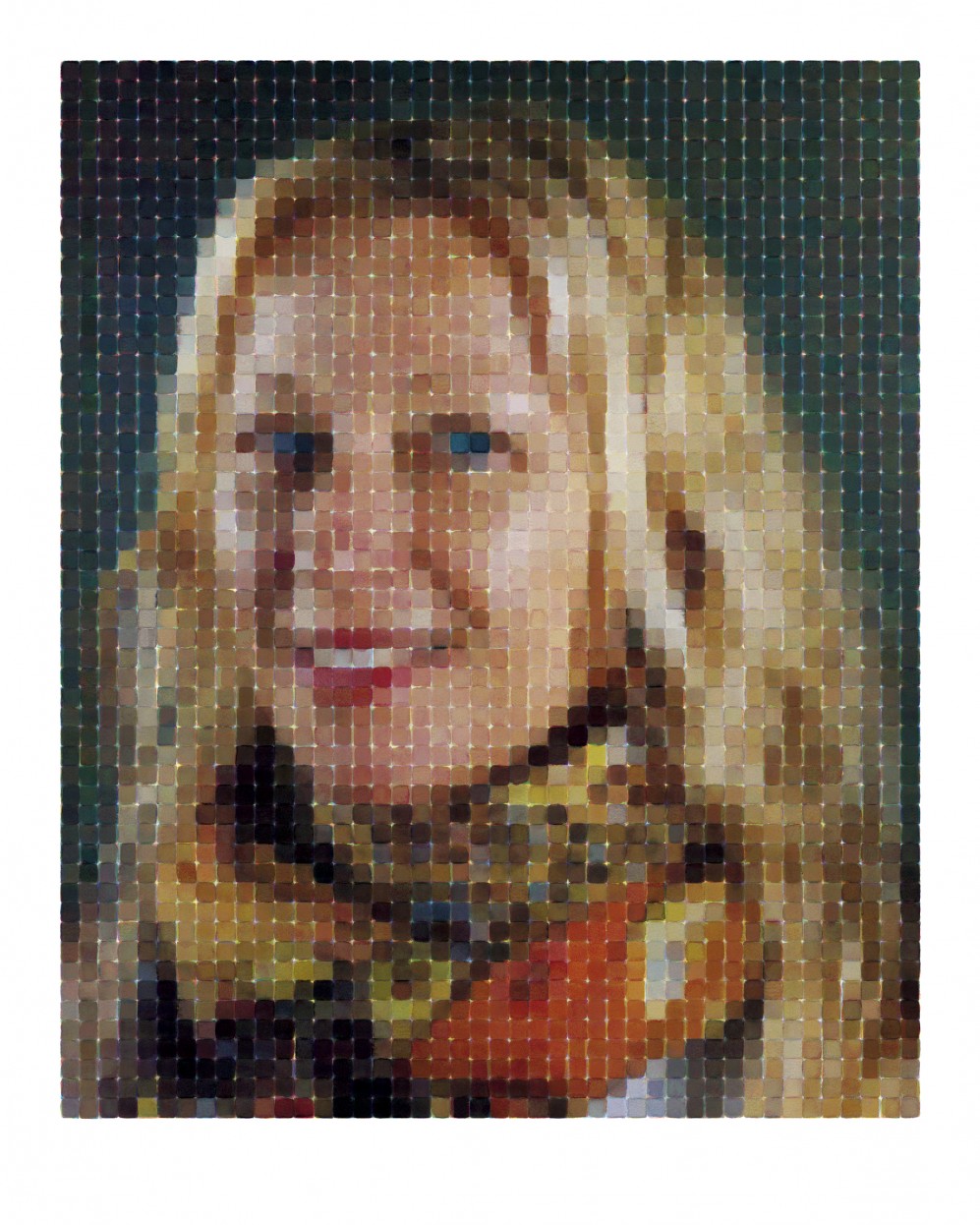

Over the years, Close’s choice of sitters has included other artists for whom portraiture is a primary practice. In this installation, a massive portrait of photographer-cum-master of disguise Cindy Sherman easily occupies one-third of a wall. Sherman’s blonde hair, bright blue eyes, and welcoming smile are pixelated by Close’s hand, her true identity further obscured. It’s evident that we are looking at a portrait, but unlike the sharp, severe clarity of a photographic print, Close’s images are built up, square by square, until viewers can see both the individual subjects and the colorful, vibrating abstractions they become at close range. The artist pays meticulous attention to the topography of his sitter’s face, each of which, one imagines, presents unique challenges.

Chuck Close. Cindy (Smile), 2013; archival watercolor pigment print on Hahnemühle rag paper; edition 5/5; 63 x 53 inches. © Chuck Close, in association with Magnolia Editions, Oakland, and Pace Gallery, New York.

Chuck Close. Cindy (Smile), 2013; archival watercolor pigment print on Hahnemühle rag paper; edition 5/5; 63 x 53 inches. © Chuck Close, in association with Magnolia Editions, Oakland, and Pace Gallery, New York.

This exhibition also allows insight into the artist’s own changing appearance as he grows older in self-portraits, the lines of age rendering his remarkable face that much more distinguished. Despite physical disability, Close’s practice has evolved, however subtly, one face at a time. While he hasn’t strayed from his grid schema and focus on portraiture, it’s clear that Close’s pursuit of a singular subject over four decades has only advanced his skill and promise as a visual artist.