Shotgun Review Archive

2nd Look - Colter Jacobsen’s Sp(out)er (In)nomine diaboli in Moby Dick

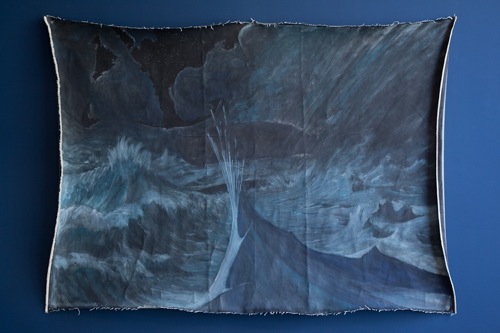

October 4, 2009 Colter Jacobsen. Sp(out)er (In)nomine diaboli, 2009; oil on canvas

Colter Jacobsen. Sp(out)er (In)nomine diaboli, 2009; oil on canvas

A boggy, soggy, squinchy picture truly, enough to drive a nervous man distracted. Yet was there a sort of indefinite, half-attained, unimaginable sublimity about it that fairly froze you to it, till you involuntarily took an oath with yourself to find out what that marvelous painting meant. - Moby Dick, Chapter 3 At the beginning of Chapter 3 of Moby Dick, Ishmael describes a unstretched painting hanging in the Spouter-Inn --an almost abstract torrent of grey, blue and black-- to be "so thoroughly besmoked", that one might take it to be "some ambitious young artist's...endeavor to delineate chaos bewitched." He learns from others that it may have originally depicted a whale being impaled on the three masts of a ship during a hurricane. All the remaining visual clues are a limp black cloud near the center of the image and three poles. What is amazing is not the precision with which Colter Jacobsen has recreated a painting from Melville's lengthy description, but the way in which he consolidates the complexity of the novel. Foremost, the abstraction of the image speaks to the unruliness of the novel. Further, it attests on its very surface to the passage of time: not only the span within the novel - the period it hung in the Spouter-Inn before Ishmael encountered it, but also the ensuing years since Melville published Moby Dick, which saw the novel itself become clouded by the soot of pop culture and academia. The painting described by Ishmael was aged and obscured by the generations of tobacco smoke rising up alongside the stories, laughter, brawls, and histories of the sailors in port. It is this intergenerational vaporized machismo which shrouds Sp(out)er (In)nomine diaboli. It is a relic of hyper-masculinity, visualizing a bond shared between men. The almost pornographic scene of the impaled whale becomes a sensitive encounter between the viewer and the artwork in Jacobsen's painting. He locates a diffused and intimate, if troubled, space within--and literally on top of--the novel's epic structure, evoking queer desire and depicting the homoeroticism that courses just beneath the book's surface. Unlike much of the other work in this exhibition, Jacobsen's painting isn't clever or cute, but consolidates many of Moby Dick's nuanced concerns. It stands out as an example of what an artist dialoging with a great work of art can do in the present moment; one that doesn't supply cheeky answers in sailor's suits, but offers a challenge, and invites us on its quest for knowing.

Moby Dick is on view at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts in San Francisco through December 12, 2009.