4.16 / The Museum, Part 1: The Mutable Object

Opening up the Museum

May 30, 2013

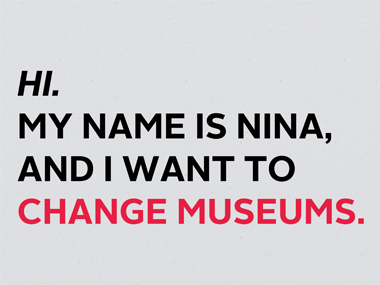

Last November, Nina Simon, executive director of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History, gave a TedX Talk titled “Opening up the Museum” at Cabrillo College Crocker Theater, in Aptos, California. Art Practical is pleased to present the following transcript of her talk, which has been edited for length and clarity. You can watch her full presentation here.

________

The passion of my professional work is about opening up museums—turning them into places that are not just places where people can visit but where they can actively participate, connect with culture, and hopefully, through those experiences, connect more deeply with each other.

For most people, museums are not seen as open spaces; they are seen as elite institutions that serve an increasingly small and limited subset of our population. We live in an incredibly fertile, creative time: people are getting together in bars to knit, renting spaces and starting businesses and doing science experiments together. When most people go looking for cultural experience, they don’t go to a museum. The research on this is very clear: throughout our country, people are more culturally engaged than ever before, but they are choosing to have these experiences outside of traditional cultural institutions. Today someone is way more likely to pick up a paintbrush than go to an art museum. Instead of going to a history museum, people are doing their own genealogical research. These are people who care about culture. As a museum director, I look at this and say, “We have to get in on this game!”

When I talk with museum professionals about this, I hear some interest, but I also hear some real concern. This is a quote from a friend of mine who works for the Smithsonian. She said, “I know a lot of people who work in art museums who would recoil in horror at the idea of being inundated by ‘Sunday painters.’” I’m sorry, but if people who paint on Sundays are not the core audience for an art museum, then I don’t know who is.

At the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History (MAH), we’ve decided we’re going to open up to participatory culture. We’re going to embrace it. Yes, we invite people to paint with us on Sundays. We encourage them to share their own creative skills with each other, and sometimes that involves tools that are a lot more extreme than paintbrushes. What I want to share are just two of the ways that we’re opening up our museum and how it’s changing both our organization and, hopefully, our community.

The first part of this conversation is about active participation. At Santa Cruz MAH, we don’t just invite people to come visit; we expect every person who walks in our museum to contribute something, to make our museum better. From the instant visitors walk in the door, they will be asked to give us a suggestion on how we can improve the museum. Over the last year, thousands of visitors have contributed content to our museum, and it’s beautiful, it’s powerful, and it’s meaningful to other people who walk in the door.

I think we all have had experiences with participatory public comment that were not so meaningful. In museums comment books are sometimes full of repetitive, boring information: “Sam was here,” “Jasmine was here,” ”Thank you very much,” etc. This kind of experience is even more familiar online. I don’t think anyone who makes pointless YouTube comments are dumb people. What I see is a lack of a designed opportunity to really invite them to give something meaningful to the situation. I believe that everyone has something really powerful and creative to add. I believe that everyone has a story to share. But I also know that everyone can be banal; we can all be idiots sometimes.

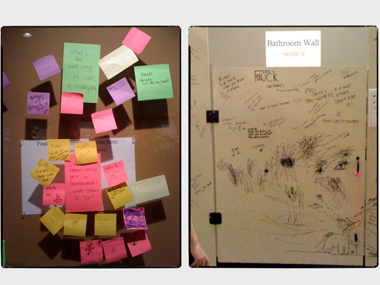

As somebody who works on inviting participation, [I know] the difference is in how we design the invitation to participate. Good design can elevate people to share their best selves in a way that lousy design cannot. Let me give you an example: I worked on an exhibition in Seattle a few years ago. The exhibition was about advice, and there were two ways in the exhibition that visitors could give and get advice. On the left, people could put up a question with a Post-it and others could respond and give suggestions on Post-its, as well. People were very well-meaning in trying to help each other out. On the right a fake bathroom door was constructed, and mostly what people did was scribble nonsense or write, “For a good time call Johnny.” Now when visitors came in the door of this exhibition, we didn’t send the well-meaning people to the Post-its and the fools to the bathroom door. The same people did both of these activities, and the reason they interacted differently was because of the design and the tools that were given to them.

Here’s an even geekier example: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art did a project a couple years ago where they asked people a question about art. They gave some visitors white cards and golf pencils and some visitors hexagonal-shaped blue cards and big pencils.

What they found was that people wrote better answers on the blue cards than they did on the white. Does this mean that blue is a magical color for participation? No. What it means is that when somebody is given a special tool, they feel valued. Showing them that what they’re going to do matters transforms what they do in return.

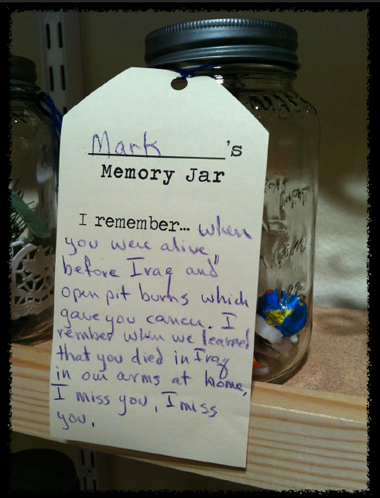

At the Santa Cruz MAH we think really hard about how to design invitations to participate in ways that encourage people to feel valued and to feel like they better give something good back. When we asked people to share their relationship break-up stories, we had them put up a Post-it on a specially painted wall. When we invited them to share their favorite memories of coffee, we gave them coffee beans to vote with so that they could smell and feel that experience of coffee. When we asked people to share love letters, we gave them a typewriter to work with, an unfamiliar tool that caused them to slow down and to share something different. As part of our memory jar installation, we gave people mason jars and craft materials and asked them to think of a personally important memory and then create a representation of it and bottle it up for somebody else to see. We had over three hundred people contribute jars in one month. I took a picture of one that reads: “I remember when you were alive, before Iraq and open pit burns which gave you cancer. I remember when we learned that you died in Iraq in our arms at home. I miss you, I miss you.” I don’t think this visitor walked into the museum expecting he was going to share this story. But this activity and the designed experience brought it out of him, and he was able to contribute something really powerful to our museum and to other visitors who walk in the door.

This kind of participation isn’t just changing the content of the museum; it’s changing the way that visitors see themselves as creative agents. We’ve had a lot of positive response to what we’ve been doing over the last year. One of my favorite quotes came from a teenager who said, “We have been to famous art museums all over the Europe, but this is the first exhibit that makes me want to do art.” I hear that and am thrilled, not just because we turned somebody onto culture in a different way, but because this is somebody for whom the museum has become relevant. This is somebody who’s going to get more involved. Over the last year we’ve seen this happen again and again. Just with one year of participation, we’ve totally changed what’s happening in our museum. From last year to this year, our attendance has more than doubled. By doing this kind of participatory stuff, we’re not just making the museum exciting; we’re making it sustainable for the future.

One might wonder, What about the objects? Aren’t museums inherently about artifacts? The second part of this conversation is how we’re transforming our museum artifacts by starting to look at them as opportunities to mediate conversations between strangers. To give you an example outside of the museum: Anyone who owns a dog has had the experience of walking a dog in public and a stranger comes up and talks to you. They’re not really talking directly to you; they’re sort of talking through the dog to you. The dog is a kind of safe, social object that mediates an encounter that otherwise wouldn’t happen.

As a museum designer, I get really curious about this type of encounter and think, How can we make museum artifacts more like dogs? How can we make them opportunities for conversations that otherwise wouldn’t happen? Because the kinds of social experiences that people can have around museum objects are bigger than the ones we have around dogs. Museum artifacts have the power to expose the big conversation we need to be having about where we have we been, where we are now, and where we are going.

At the Santa Cruz MAH we think really carefully about how to bring to life conversations around these objects, whether that’s through a craft activity that gets people deeply involved with the work or through an activity that invites them to select which objects are relevant to our community or through designing a game that invites people to engage more with the work. All of these activities help people connect with the artifacts and learn more about them, but more importantly to me, they help people connect with others who are not like them. A powerful social object can bridge a gap that otherwise may not be crossed.

When we do this work, when we invite people to participate, when we see objects as [loci] of conversation, we can transform museums from things that are nice to have into things that are really necessary to move our communities forward. This isn’t just happening in Santa Cruz. It’s happening all over the world. In Toronto, at the Ontario Science Center, they’re inviting visitors to invent solutions to global problems. In Minneapolis, at the Institute of Art, every ten years they have an exhibit where they say everybody and anybody in the community can bring in a small artwork and they will hang it on the wall of a world-class museum. At the Brooklyn Museum of Art, they’re using technology to experiment with new ways for people to engage with artifacts and with each other.

When I look at any of these examples, what I’m looking at are the people. When people at my museum are doing a craft activity together, I don’t just see people cutting up magazines, I see people who come from different walks of life, brought together through a cultural experience. Perhaps one of the most powerful experiences I’ve seen in Santa Cruz is happening outside of the museum. About a year ago, the Santa Cruz MAH teamed up with a homeless service center, and every Monday museum volunteers and homeless volunteers come together to help restore Evergreen Cemetery, an important historic site. Together, they’re beautifying it, they’re making it safe, and they’re literally uncovering history as they reveal gravestones of Santa Cruz’s founders. Everybody who comes out and works at Evergreen has a powerful experience with history. More importantly, everybody who comes out to Evergreen has a powerful experience with somebody who is not like them, somebody who they might be fearful of in another situation. It’s this kind of social bridging that culture can enact so powerfully and so importantly for us today.

We live in a really divided world, politically, economically, and culturally. I feel that we desperately need places that allow us to have positive interactions with people who are not like us. What we’re doing right now at the Santa Cruz MAH is not about the experiences that happen inside the museum; it’s about how these experiences transform the ones people have when they go outside. I dream of a time when everyone can participate in our museum, can connect with culture, and can walk out and have a better connection with somebody else on the street.

All images courtesy Nina Simon.