3.21 / Best Of: Year Three

Best Of: crystal am nelson

August 16, 2012

Image: Kalup Linzy, in front of a poster for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art's production of Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson's Four Saints in Three Acts. Courtesy of SFMOMA. Photo: Megan Brian.

Best Consistent Art Programming

Beginning with its updated version of Virgil Thompson’s and Gertrude Stein’s avant-garde opera Four Saints in Three Acts, which featured the rising video and performance artist Kalup Linzy, and ending with a career retrospective for the renowned photographer Cindy Sherman, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) has had a landmark year that only got better as it progressed. Much of the credit is due to Sandra S. Phillips, the museum’s long-time curator of photography, who brought to the Bay Area some of the most exemplary talent in the medium. Other highlights include: the first posthumous retrospective in two decades of the young and prolific Francesca Woodman, who in her twenty-two brief years created an exhaustive body of work that examines not only femininity, the body, and space but also what it means to be committed to one’s art practice; the retrospective of Rineke Dijkstra, whose photographs and videos are wonderful, at times disturbing, meditations on the passage of youth; and the 2011 Society for the Encouragement of Contemporary Art (SECA) award exhibition that included two of my favorite artists, Kamau Amu Patton and Mauricio Ancalmo, both of whom explore the limits of technology as a meditator of personal and interpersonal experiences.

Best Visual Explorations of the Dark Side

I am obsessed with the dark and macabre, and I love the type of horror that hides just beneath the seemingly banal. I have seen few artists capable of rendering this in ways that are as beautiful as they are frightening, and San Francisco–based Christopher Burch and Christopher Charles Curtis are two such artists. I met Burch while we were working toward our MFAs at San Francisco Art Institute, and I was immediately taken by his nightmarish reworking of blackface caricatures. His multilayered drawings and large-scale paintings depict the psychic prison created by the intense anger and deep sadness experienced from ongoing encounters with the mostly insidious and sometimes violent racism that continues to pervade this country. Where other artists might lean too heavily on didacticism, Burch’s articulation of racism’s emotional reverberations allows the medium to function as an integral element of his message.

Burch introduced me to Curtis, also known as C3, whose graphite drawings reveal a mind as obsessed with the macabre as mine. C3 works from photographs, some found and others created, that depict the grotesque and gothic. Besides the impeccable execution of his drawings and his deliberate choice of substrates—toe tags, to name just one—I am also impressed by C3’s profound subversion of Americana and the attendant misty-eyed nostalgia. By using familiar, vintage tropes associated with a presumably simpler, safer era in this country, he suggests that danger, violence, and terror have always been a part of our cultural and psychic landscape and may always be.

Best Regional Art Initiative That Didn’t Happen in the Bay Area But Should Have

Pacific Standard Time (PST) was a six-month initiative of the Getty Research Institute that brought together more than sixty art institutions in Southern California to celebrate the birth of the Los Angeles art scene. Featuring approximately one thousand three hundred artists who were active in the L.A. area during the postwar years, the initiative mounted exhibitions in major museums and galleries throughout the region. A small selection of noteworthy exhibitions include: Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980 (Hammer Museum); Asco: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972–1987 (Los Angeles County Museum of Art); Doin' It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman's Building (Otis College of Art and Design, Ben Maltz Gallery); and L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema (University of California, Los Angeles Film and Television Archive). There are many other impressive exhibitions, but for the sake of brevity I selected the above because they represent one of the keys to PST’s success: diversity. Much attention was given to the significant contributions of Chicano, African American, female, and queer artists to the development of art and culture in Los Angeles, something that until this project was largely absent from art history.

This matters to us because the Bay Area is long overdue for a similar initiative with a similar level of consideration for underrepresented artists. Many in the Bay Area fail to see the importance of multiculturalism and equal representation in the arts, and some people have gone so far as to say that prioritizing diversity reduces the quality of museum programming. The Getty has proven those complaints erroneous and witless. Although Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA) has the triennial art festival Bay Area Now (BAN), its breadth is narrow. BAN, the sixth installment of which closed in October 2011, generally includes around twenty visual artists from the entire Bay Area—but mostly from San Francisco and the Art Murmur scene of Oakland—in addition to performance groups and filmmakers. As a former YBCA employee, I do not wish to unnecessarily add to the criticism of BAN over the years, especially since I know well the internal debates surrounding the festival. YBCA’s curatorial team is deeply concerned with presenting an inclusive, substantive program. However, after working through two BAN festivals during my tenure, I think its challenges include adhering to the triennial format and working alone to represent such a vast region. The Bay Area has a wealth of arts institutions, from Napa to Santa Cruz; they may not have YBCA’s budget or capacity, but they may be interested in collaborating on a regional initiative that celebrates the Bay Area’s artistic heritage. YBCA is uniquely positioned to spearhead such an endeavor.

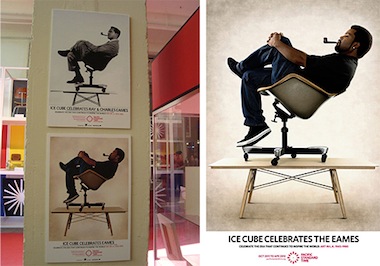

Promotional posters for Pacific Standard Time featuring Charles Eames' sitting in his DAT chair (c. 1953) and Ice Cube recreating the photo. Courtesy of Adrian Glick Kudler.

Best Live Sex Show

My Best Of list would not be complete without including something about sex. Yes, I am a pervert, and no, I am not ashamed to admit it. Thankfully, in a city like San Francisco, perversion is almost a prerequisite for residency and there are plenty of options to satisfy everyone’s kinky proclivities. Identifying the best among these is a challenge, but Kink continues to wield its pornographic might in this arena. For six years, Kink has been churning out all manner of BDSM content to satisfy almost every fetish from its fortified headquarters at The Armory on 14th and Mission Streets. In addition to its web programming, Kink also hosts an extensive roster of on-location programs for the voyeur in each of us. My favorite is Ultimate Surrender, an all-female wrestling match that pits women in a fight to the fuck. Excuse my French, but there is no other way to describe what the winners get to do to the losers. The main objective is to score as many points as possible through the stripping and forced (sexual) touching of the opponent. For first-time viewers, it is discomfiting to watch women sexually assault each other for a live audience. But the viewers’ awkwardness wanes after they realize that the true contest is about who can stave off arousal long enough to score points. The custom-designed arena is rigged with cameras strategically placed to capture the wrestlers and the audience, who are expected to encourage all manner of touching. Mounted to the wall is an official clock and scoreboard, and two referees, dressed in authentic uniforms, monitor the match from the floor. It is all very official, very good, filthy fun.