Features

Stranger Visions: Questioning Tech’s Ethics in a DNA Boom

November 13, 2018In-depth, critical perspectives exploring art and visual culture on the West Coast.

The term stranger implies an unknowing, a transient space of identity, and a comparative unease. We are all strangers in a public space, and nothing is stranger than entering into an exchange one didn’t agree to. Traces of our bodies are littered across city streets. A private life is made evident in sidewalk cracks, curb cuts, and gutters: a piece of gum, a strand of hair, a cigarette butt, shed skin. What if this physical record could be tracked and attached to someone, like a digital footprint? What if it already is?

In the shadow of Silicon Valley, identity is commodified as an architecture of preference-based data. A tacit exchange of information, connection comes at the price of user-driven data collection. Each week in the Bay Area, a new tech startup offers utopian ends from its data hoard, ranging from product recommendations and traffic routes to pharmaceutical research. Each week also brings headlines regarding privacy breaches and data misuse.

Merging accumulations of data with the traces of our genes, the Silicon Valley-based consumer-genomics company 23andMe offers genealogy and health reports in exchange for a small fee and a vial of spit. At the company’s lab, DNA is extracted from the spit and, using a process called phenotyping, is transcoded into predictions about the past and, potentially, the future of the donor.

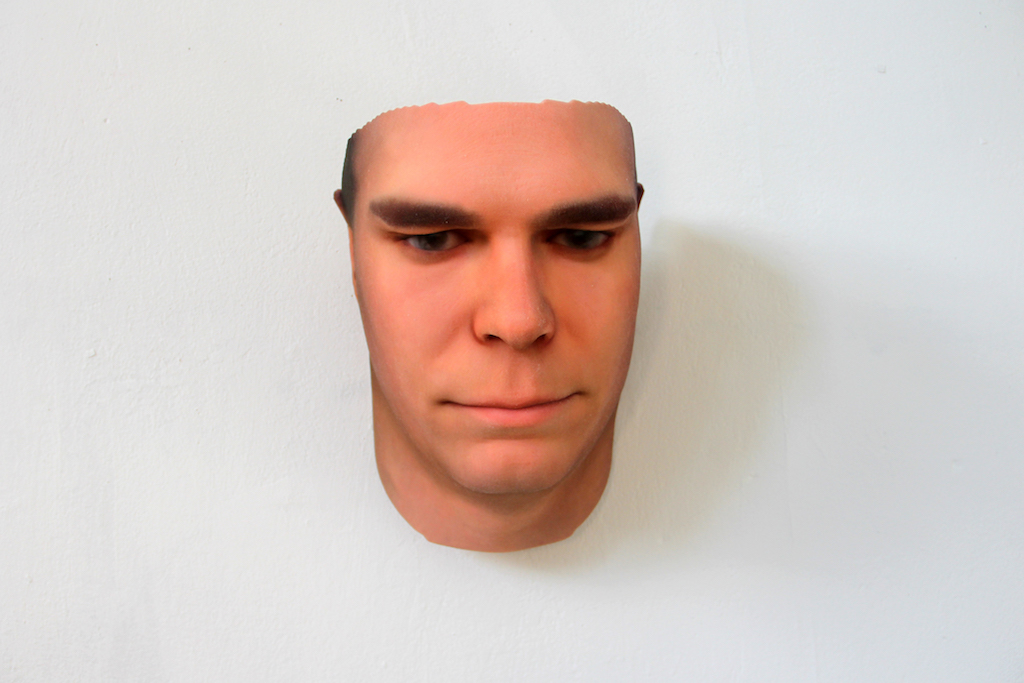

Heather Dewey-Hagborg. Stranger Visions, 2012–13; found genetic materials, custom software, 3D prints, documentation; dimensions vary. Courtesy of the artist and Fridman Gallery, New York, NY.

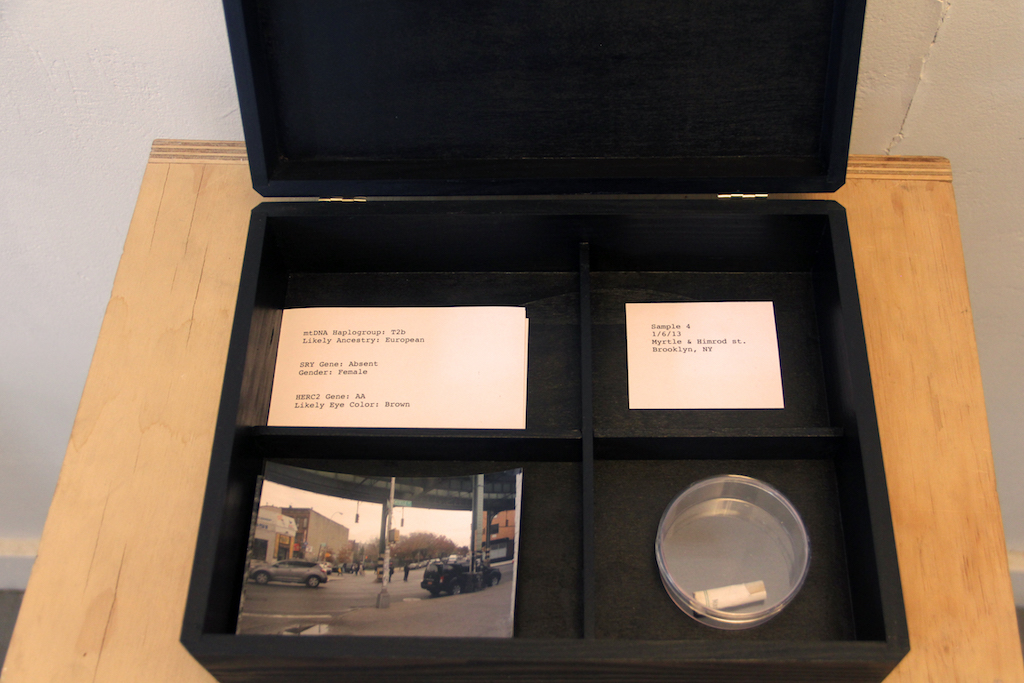

Heather Dewey-Hagborg. Stranger Visions, 2012–13; found genetic materials, custom software, 3D prints, documentation; dimensions vary. Courtesy of the artist and Fridman Gallery, New York, NY.

To see a health-data report from 23andMe requires clicking through an online user agreement. Consent through the company is twofold: one, that its interpretation of health data is only an indicator, and that knowledge of this data can affect the worldview and relationships of those who share their DNA; and two, that 23andMe shares parcels of phenotyped DNA and self-reported data with third-party pharmaceutical and medical-research companies.1 The business model of data harvesting and selling to third parties is a direct parallel to internet giants like Facebook and Google. Not surprisingly, one of the top investors of 23andMe is Google’s co-founder, Sergey Brin. This investment partnership prompts George Whaley and Stephen McGuire’s unnerving question: whether “Google, in the business of acquiring users’ web-browsing data, might also have access to genetic data—and the ability to match the two.”2 What happens once a private identity—ranging from one’s conscious preferences all the way down to one’s genes—is parceled for profit and, in the process, opened to a potential privacy breach?

The artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg spent 2012 and 2013 collecting genetic traces left on New York streets and meticulously annotating each acquisition, for her project Stranger Visions. The artist extracted DNA from the collected detritus (hair, gum, cigarette butts, etc.) and employed a phenotyping algorithm trained to detect specific genetic motifs and to generate predictions about the individuals who unknowingly left their DNA behind: their eye, skin, and hair color; biological sex; and facial structure. Then, using 3D-modeling and commercially available software, such as FaceGen, the artist generated mask-like portraits of each subject. When exhibited, the portraits are displayed with an evidence kit containing photos of the collection site, a printed summation of the phenotype analysis, and the collected DNA object in a petri dish.

Each portrait in Stranger Visions has distinctive features, but, as the subjects are anonymous to the artist, their imaging is largely subject to the inherent biases of phenotyping software and the algorithms that determine much of our digital lives: the software merely matches data to the samples at hand. Algorithms function on the presumption of sameness. The closer the user is to a central norm, the better the algorithms’ predictions are.3 With our present knowledge of genetics, phenotyping algorithms are similar to stereotypes in their oversimplification.

From object to subject, Dewey-Hagborg’s portraits carry a hollow absence. The thin mask-like forms expose their medium as 3D prints, digitally rendering the softness of flesh as hard striations. The hair of each subject is cropped away, leaving a stepped, rigid line at the top of the forehead. The influence of our genes on many phenotypic traits, like the appearance of our faces, isn’t fixed as a series of codes.4 The lives we live can be more influential than our genes alone. Wrinkles, scars, hair color and style, plastic surgery, eyeglasses, piercings, tattoos, and cosmetics are determined by environment and lifestyle rather than genetics. As Dewey-Hagborg says, “Identity is how we define ourselves while traits are categories imposed or inscribed onto our bodies from external sources.”5

By transforming anonymous DNA into distinct, physical representations, Dewey-Hagborg’s Stranger Visions visibly renders the ethical ramifications of DNA interpretation. What was in 2013 a speculative fiction now, in 2018, inches closer to reality. Soon strangers, no longer anonymous, may be non-consensually identified through commercial biobanks.6 The ties to the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica data breach, whereby the data of 87 million individuals was gathered through friend-list connections to 270,000 initial users, run eerily parallel.7

Like the shed DNA lining city streets, internet data collection leaves a trail through which to trace our digital lives. Without individual consent or choice, data becomes a liability, a new technology to be exploited by biopower and its corollary, bio-surveillance.8 Stranger Visions has encouraged conversations about genetic privacy. Still, little progress has been made in regulating the use and dispersion of biodata. (Dewey-Hagborg’s current projects do include a framework for genetic privacy protection.9)

Technological progress is often perceived as just that: a forward march to a better world. While direct-to-consumer genetics companies like 23andMe have the potential to contribute great strides in health research and offer one component of optimization and customization of our bodies and our lives, critical issues remain unresolved. In the wake of data and DNA accumulation may lie loss of privacy, loss of meaningful consent, and even a loss of an identifiable ownership and complexity of self, whether through aggregated data of individual preferences and choices or through the building blocks of individuation, one’s genes.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg. Stranger Visions, 2012–13; found genetic materials, custom software, 3D prints, documentation; dimensions vary. Courtesy of the artist and Fridman Gallery, New York, NY.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg. Stranger Visions, 2012–13; found genetic materials, custom software, 3D prints, documentation; dimensions vary. Courtesy of the artist and Fridman Gallery, New York, NY.

Currently genetic surveillance still amounts to something of a science fiction, but the gaps between fantasy and reality are closing rapidly, and few regulations are in place to protect volunteered genetic information. Without a critical approach toward phenotyping tools and their use in the present, the future of public life may be radically different. Stranger Visions and Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s ongoing artistic investigation into the use, misuse, and abuse of phenotyping algorithms and genetic privacy offer a necessary subversion by using the means to question the ends.