Features

Michael Richards’s Alchemical Performances of Blackness

March 20, 2019In-depth, critical perspectives exploring art and visual culture on the West Coast.

Michael Richards: Winged, a solo exhibition at the Stanford Art Gallery, offers a majestic display of the artist’s sculptural and embodied ruminations on the past, present, and future. Richards used his own body as casts for many of these works, transforming sculpture and performance into a shared expanded field. Curated by Alex Fialho and Melissa Levin, the exhibition functions as a choreographed performance space of ritual memory. One of Richards’s most known works, Tar Baby vs. Saint Sebastian (1999), is sculpted from his full body, posed in a standing, meditative posture while miniature planes referring to the Tuskegee Airmen pierce into him. Given the artist’s tragic death during the 9/11 attacks while working in his studio on the 92nd floor of Tower One of the World Trade Center, the work’s prophetic nature sets the tone for the exhibition.

Winged

Upon entering the expansive gallery, I sense an ethereal presence to my left: Winged (1999). In this work, made from bonded bronze and metal, feathers that pierce through flesh function as armature and adornment. Richards’s musculature floats while feathers protruding from his forearms and wrists hang like strange fruit.1 The arms’ metamorphosis disorient me: two become one. In this compositional gesture, they appear relaxed, as their hands offer a caress. This sculptural document of performance refers to ritual piercings, from ancient practices to the artist’s engagement with blood aesthetics.2 The conjoined feathered limb also functions as a visual synecdoche for Black Indians throughout the diaspora, like the flamboyantly adorned warriors in lush feathers, bodying forth through the streets of the wicked, southern City of the Dead.3

Michael Richards. Winged, 1999; bonded bronze and metal; 20 x 38 x 4 in. Courtesy the Michael Richards Estate. Photo: Henrik Kam, Stanford Art Gallery.

Michael Richards. Winged, 1999; bonded bronze and metal; 20 x 38 x 4 in. Courtesy the Michael Richards Estate. Photo: Henrik Kam, Stanford Art Gallery.

The Transformative Power of Hair

Directly opposite Winged appears a form of shadow theater created by five Tuskegee Airmen pilot caps meticulously crafted from hair. Instead of being suspended by wire, like the floating limbs of Winged, the caps are held by microphone stands. On this ghosted stage, shadows of souls multiply on the white wall. Appropriately titled The Great Black Airmen (1996), the work stages a spectacular duality of bodies: the noble pilots in flight and the doo-wop bands of the same era. In the work’s positioning of the aerial feats of the dignified warriors alongside the battles fought by the musicians adorned in their extravagant hairdos, Black hair affectively becomes armor.4 Viewing the work from each side, I remain attentive to the postures of The Great Black Airmen, who were not only African Americans but also Haitians and Dominicans: Afro-Latino-Caribbeans, like Richards himself.5 As I reflect on the combination of words, “Tuskegee” and “Black Airmen,” I imagine that some of the pilots might have been aligned with Tuskegee Indians, thus expanding the genealogies of Black and Brown alliances.6 This stage of ritual memory thus prompts another sighting of Black Indians.

Michael Richards. The Great Black Airmen, 1996; wax, plaster, hair, steel; dimensions variable. Courtesy the Michael Richards Estate. Photo: Henrik Kam, Stanford Art Gallery.

Michael Richards. The Great Black Airmen, 1996; wax, plaster, hair, steel; dimensions variable. Courtesy the Michael Richards Estate. Photo: Henrik Kam, Stanford Art Gallery.

On the other side of the singing souls of The Great Black Airmen, a smaller diorama resides. Seemingly simple in its minimalist display, and smaller in scale than the other works, Travel Kit (1999) is at once monumental and intimate. In this disorienting configuration, fourteen bronze fingers perform as bristles on two hairbrushes resting in the wooden box’s red-velvet interior. From underneath the fingers emerge strands of hair. As if performing a surrealist puppet show for the viewer, Richards composes the hair in its procession from the body, provoking both disgust and awe.7 The miniature installation enacts a haunting transmogrification reminiscent of the body-fragment souvenirs passed around to spectators in the aftermath of public lynchings.8 The fingers beckon us into this tactile space of memory. They ask us to touch, to grasp, and to connect. Suddenly my own fingers are compelled to move toward them, mirroring their gestures.

Michael Richards. Travel Kit, 1999; bonded bronze, hair, and wood; 13 x 6 x 13 in. Courtesy Lower Manhattan Cultural Council and the Michael Richards Estate. Photo: Etienne Frossard.

Michael Richards. Travel Kit, 1999; bonded bronze, hair, and wood; 13 x 6 x 13 in. Courtesy Lower Manhattan Cultural Council and the Michael Richards Estate. Photo: Etienne Frossard.

Minstrel Shows and Lynching Shows

Other works invite viewers into the realm of present pasts. In A Loss of Faith Brings Vertigo (1994), photo-transferred images of Rodney King are placed on the third eye—the seat of memory—of a rotating bust made from marble dust, cast from the shape of Richards’s head.9 While this central bust rotates, four others appear frozen in time, placed above the words, “When I was young, I wanted to be a policeman.” Despite dreams deferred and busted, the heads remain uplifted. Their gazes seem to pierce through closed eyes, activating our own memories.

Black lives, mattering then and now, perform on the forgotten side of history. In a work nearby, Same Old Song and Dance (1992), lynched minstrels perform as documentation, to remind us of this history. This dance repeats. The “love and theft” dialectic that characterized nineteenth-century minstrel shows takes residence in Gucci-style black masks on white skins, for sale—$890, to be exact. It repeats among today’s politicians in blackface, who lead the nation founded upon the exploitation of Brown and Black bodies.10

Michael Richards. Same Old Song and Dance, 1992; mixed-media installation with motors and audio loop; dimensions variable; installation view, 1992. Courtesy the Michael Richards Estate.

Michael Richards. Same Old Song and Dance, 1992; mixed-media installation with motors and audio loop; dimensions variable; installation view, 1992. Courtesy the Michael Richards Estate.

In the original 1992 installation (on view at Stanford in video documentation) of Same Old Song and Dance, composed of two window displays, Richards’s minstrels’ masks are intentionally not visible. One window stages a haunting image that echoes the strange fruit of the Winged feathers nearby: rotating ever so slowly are the hanging legs of four mannequin minstrels in sleek black slacks and shiny shoes. The other window stages twelve rotating busts, like those presently on display in A Loss of Faith Brings Vertigo. The visual narratives of blackface shows and lynching shows become one on this stage of ritual memory while the work gestures toward their continued legacies in the form of modern-day police brutality.

Soaring Above

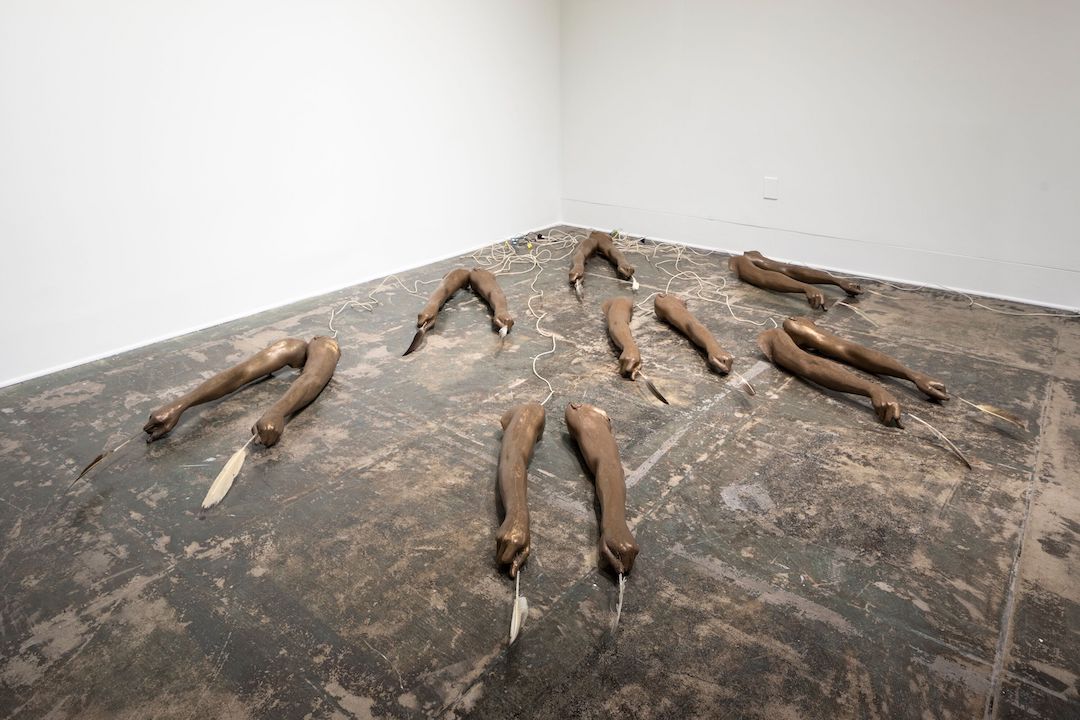

At the far end of the gallery, I encounter Fly Away O’ Glory (1995), diagonally across from and directly in conversation with the memories encased in Travel Kit. Here, remnants of the strange fruit have fallen to the ground. Seven pairs of arms made from bronze resin rest on the floor, their hands gently holding feathers. Every fifteen seconds the feathers are mechanically activated, spinning around like the rotating busts and Tuskegee plane propellers throughout the exhibition. Each spin cycle invites another intake of breath. Fly Away O’ Glory also echoes Winged at the entrance of the gallery, where feathers pierce through skin rather than gesture toward flight. The placement of these two works thus provides a dialectical framing for the show, in which Richards confronts the dualities of ascent and descent: limbs that sink into the Earth are propelled upward, taking residence among ancestors.

Michael Richards. Fly Away O' Glory, 1995; resin, bronze, feathers, motors; dimensions variable. Courtesy the Michael Richards Estate. Photo: Henrik Kam, Stanford Art Gallery.

Michael Richards. Fly Away O' Glory, 1995; resin, bronze, feathers, motors; dimensions variable. Courtesy the Michael Richards Estate. Photo: Henrik Kam, Stanford Art Gallery.

Michael Richards: Winged is a poetic documentation of the artist’s intimate engagements with materiality and temporality. His works reflect the alchemies of performative Blackness, transforming the matter of minstrel shows, aerial shows, and public lynchings into layered imagery that simultaneously conjures historical trauma and resilience, from diasporic Black Indians to doo-wop musicians. Winged and propelled in multiple directions, Richards soars above and below. He persists as a futurist sculptor of history, equipping his audiences with weaponry in the form of memory, so that we, too, may continue to propel the work of re-imagining the future in light of remembrances of the past.

Michael Richards: Winged is on view at the Stanford Art Gallery in Stanford, CA, through March 24, 2019.

________

I thank William Cordova and Dread Scott, two friends of Michael Richards, who provided critical background information; Jakeya Caruthers, Michele Elam, and Rose Salseda for their inspirational quotes during the Stanford symposium cited in the notes; Donna Hunter and Becky Richardson, my colleagues from the Program in Writing and Rhetoric at Stanford, for their feedback; and Anne Shulock, Art Practical contributing editor, for her insightful comments and suggestions.