Features

Ceci n’est pas un mot: It’s Word Art

April 24, 2018In-depth, critical perspectives exploring art and visual culture on the West Coast.

As if abandoned upon the vast territory of graph paper—stained, as if painted; worn, as if shadowed—the sentence’s lilting cursive script edges toward the border of the photograph. It is this visual performance that draws me from across Pier 24 Photography’s gallery,1 but it is the sentence, as complete as Hemingway’s purported story, “For sale, baby shoes, never worn,” that yanks me in:

If there was a nice apartment and I

have a descent job and you felt happy and

thought there could be a ^nice history together, would

you come home?

If either the image or its words in Alec Soth’s Would you come home? (2005) might threaten to dominate, the other holds its own, turning battle into dance, and the artwork into a record of this interplay. Even within the image-drenched culture of the US mainstream, words take precedence in determining meaning. Yet in the visual hothouse of the gallery, word art—particularly the word art of artists whose language fosters ambiguity—faces enormous challenges. Can an artwork’s visual and verbal impacts co-exist and survive each other's force?

Alec Soth. Would you come home?, 2005, from the NIAGARA series; archival pigment print; 30 x 24 in. © Alec Soth, courtesy of the Artist.

Alec Soth. Would you come home?, 2005, from the NIAGARA series; archival pigment print; 30 x 24 in. © Alec Soth, courtesy of the Artist.

Ignore the misspelling of “decent.” Spelling doesn’t matter. Don’t ignore the sentence’s slippy-slidey temporality as tenses flex upon each other. After all, language deploys whatever idiom is ready at hand, withstanding the judgment of grammatical impropriety.

The opening “If” situates the reader beyond the present moment; “there was” attains both the past’s “had been”—implying that once there had not been a nice apartment—and the future’s aspirational “were,” suggesting that there might someday be, especially if “I have a descent job.” The presentness of “have” contradicts the pastness of “was,” while the futureness of “If” alludes to both the past’s I once did not have a decent job as well as the future’s but I can, and will, if only you would come home. The sentence continues to circle back upon itself until the reader gets to “and thought there could be a ^nice history together.” The future anticipated by “If” becomes “history” because the writer, grabbing the idiom at hand, transports the reader into that future, promising that the view backward will reveal the history as having been “nice.” The caret marks “nice” as an afterthought. But it also marks a revision, a reference to our past (a not so “nice”—but maybe a little bit nice—history) and our caret-signaled future of niceness. The sentence’s shifting tenses pile up, all present in the same moment, rebuking then redeeming each other.

In whose possession is the letter? The writer, who never sent or signed the missive? Or the recipient, who needed no signature to know who tendered this package of love and longing? The letter’s “mistakes,” which make the authoring process so palpable, and the immense space of the ^incomplete page ask me to read the words as if I were the author, the letter as unfinished. But the brown stain and the gray discolorations—oil? water? tears?—signal the passage of time, the process of reading.

Alec Soth. Tricia and Curtis, 2005, from the NIAGARA series; archival pigment print; 24 x 30 in. © Alec Soth, courtesy of the Artist.

Alec Soth. Tricia and Curtis, 2005, from the NIAGARA series; archival pigment print; 24 x 30 in. © Alec Soth, courtesy of the Artist.

I did not need Soth’s portrait, Tricia and Curtis (2005), to embody letter writer and recipient. But across the gallery, and despite everything, they hold themselves together: past, future, and present. Their faces, weary, wear almost-smiles. Their bodies, comfortable with each other, repose. Their disappointments drape over them. All of this contracts into a visual representation of “relationship.”

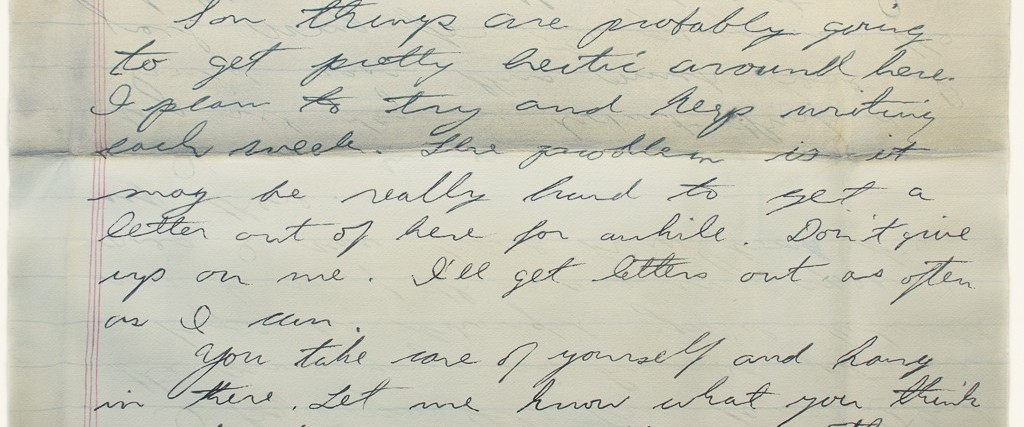

Son things are probably going

to get pretty hectic around here.

I plan to try and keep writing

each week . The problem is it

may be really hard to get a

letter out of here for a while. Don’t give

up on me . I’ll get letters out as often

as I can . ...

Michael Hall’s Pretty Hectic (2016), a watercolor painting of one of the artist’s father’s Gulf War letters, like Soth’s photograph, reminds me that art delivers meaning from both its rootlessness—its capacity to exist only in this moment, with only my mind to limn its contours—and its context. Soth’s NIAGARA series—which includes Would you come home? and Tricia and Curtis—inhabits the realm of, as Soth puts it, “passion and its aftermath,” a formula that encompasses both the force of love between humans, and the deindustrialization and dislocation of rural American towns like Niagara Falls.2 Haunting Pretty Hectic and the other works in Hall’s Correspondence and Reclamation series is war: the 1990–1991 Gulf War; World War II, as evoked by decaying and decommissioned Bay Area 1940s army installations in Watchtower, FB-BA-PB (2010); and Vietnam, which Hall’s father mentions in another letter.3

Michael Hall. Pretty Hectic, 2016; watercolor on paper; 22 x 30 in. © Michael Hall, courtesy of the Artist and the Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, University of California, Berkeley.

Michael Hall. Pretty Hectic, 2016; watercolor on paper; 22 x 30 in. © Michael Hall, courtesy of the Artist and the Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, University of California, Berkeley.

That both artists can deliver so much without forcing the context is a result of their skillful application of the word art form. We can’t know precisely what Hall’s dad meant when he wrote, “Don’t give up on me. ...” I imagine states of sadness and longing, anger and fear, the desire for love and the cling to hope, the struggle to reclaim relationships before disuse or even death snatches them away. But perhaps Hall’s dad meant only that it was a trial to sustain a consistent correspondence.

Hall titles each letter painting with his father’s words. Pretty Hectic reflects both his father’s adult situation and what I sense must have been Hall’s own adolescent condition.4 In both contexts, “pretty hectic” becomes an apt euphemism for the stuff—all that “^nice history”—that struggles to express itself. We say things are “pretty hectic” when we mean what Tricia and Curtis’s complex gaze delivers more directly. And so, between Hall’s dad’s lines, I read not necessarily what he meant but what my mind imposes: stories within stories within stories. I imagine, even, that Hall’s concrete bunker paintings, which share the space at UC Berkeley’s Townsend Center, illustrate some semblance of “the interpersonal landscape of a father and son’s relationship stretched thin by war,”5 as well as Hall’s dad’s attempt to bridge time and place.

Michael Hall. Watchtower, FB-BA-PB, 2010; oil on canvas; 72 x 60 in. © Michael Hall, courtesy of the Artist and the Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, University of California, Berkeley.

Michael Hall. Watchtower, FB-BA-PB, 2010; oil on canvas; 72 x 60 in. © Michael Hall, courtesy of the Artist and the Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, University of California, Berkeley.

Hall’s and Soth’s processes are distinct, but both artists create a container for a linguistic artifact, which without that container would not survive the gallery. Hall’s transformation of the letter into something other is all the more complete as it gets closer and closer to a facsimile of the actual letter itself. The painting duplicates the horizontal and vertical shadow lines, the bleed-through of writing from the other side, the printed blue and red ruled lines, the torn top and bottom edges, the handwriting’s variations in darkness and lightness, and the strange little space that Hall’s dad habitually inserts before almost every period. All of these elements, rather than appearing as extraneous visual detail, puts the page into my hands, elevating its meaning.

ONE

AN

OTHER

ONE

OTHER

ONE

AN

OTHER

ONE

OTHER

AN ONE

ANOTHER

ONEANOTHER

ONANOTHER

Soth’s and Hall’s word artworks, which present whole texts that once unfolded independently of their depictions, seem distant from the characterizations of commentators like David Galenson, who describes the 20th-century use of language in visual art as both the cause and effect of the rise of conceptual art, tracing a trajectory from Braque and Picasso through to Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer.6 Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Repetitive Pattern (1975) is more consistent with a history in which words reduce themselves to word forms and visual wordplay.7 Yet, all three artists strong-arm language: ceci n’est pas un mot!8 Soth’s writer tumbles tenses. Hall’s edits out as much as he scripts in (is that what those little spaces mean ?). And by repeating “one another,” Cha unhinges those two simple words from the simplicity of their definitions. In any of these three versions of ambiguity, it’s nevertheless hard to avoid the meaning that the artworks communicate as much visually as verbally: that of longing and belonging.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. Repetitive Pattern, 1975; ink on cloth, with thread; 46 x 46 in. Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, gift of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Memorial Foundation. Photo: Benjamin Blackwell.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. Repetitive Pattern, 1975; ink on cloth, with thread; 46 x 46 in. Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, gift of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Memorial Foundation. Photo: Benjamin Blackwell.

Cha found her inspiration in, among other things, the concrete poetry movement,9 which marries the text’s form and its language to engender meaning. Designated “ink on cloth,” Repetitive Pattern appears as a sort of calligraphy until the additional “thread” reconceives it as tapestry. The label highlights the repetition of sewing—a piecing together—and a sort of desperation to say and say again (with the hope that again-saying will say it differently). As with Soth and Hall, it is Cha’s wordplay and its depiction that reminds us of the struggle to be with an other.

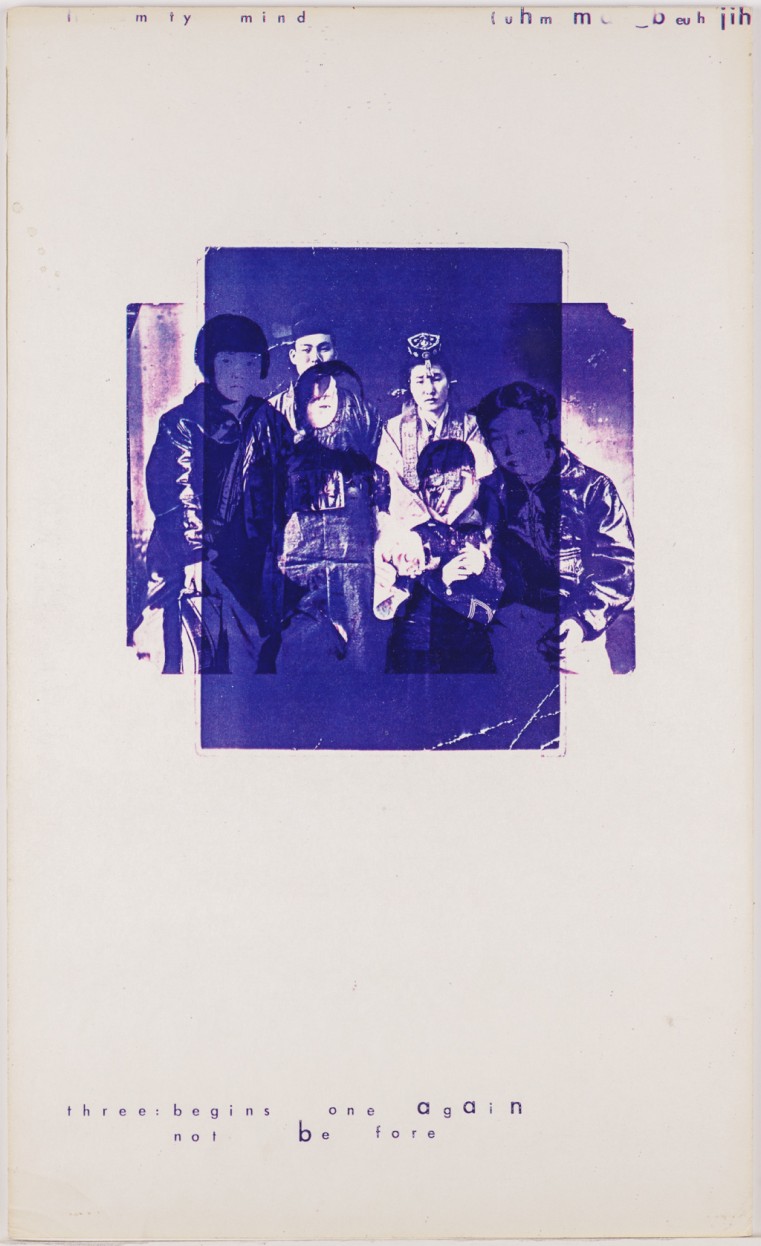

Crowding around all the works at Cha’s exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive is the Cha family’s 1963 flight from post-coup Korea when Cha was 12 years old. Cha memorializes displacement in the eighteen panels of Chronology (1977). Each panel hosts color photocopies of family photographs and a typographically animated, concrete poetry caption such as: “three:begins one again not be fore” and “not be named knew heard. partache/ake.”10 Transcribed here, these lines fail to explain either their photographs or their typographical layout, but they reveal a kind of order that spirals toward linguistic and visual disorder, and a piling on of family relationships.

Cha forces us to see beyond our assumptions about language, revealing it as defiant of dictionary definitions of repetition, chronology, and family. In this way, Cha goes further than Soth or Hall, letting her language migrate away from linguistic meaning, linking her to artists and poets who have completely freed word form from the word.11

If histories like Galenson’s tell one version of the relationship between image and word, 18th-century thinker Gotthold Lessing tells a different one, characterizing literature as temporal and visual art as spatial.12 Soth, Hall, and Cha, however, manifest perfect rejoinders to both of these theories: word art cannot live by words alone. In the presence of their artworks, viewing and reading tumble over each other, as if Lessing’s imagined rivalry were being played out in front of us, revealing itself as an embodied improvisation in which each activity both leads and follows. The only sensible response for the reader-viewer is to tumble along and join the dance.